After the October Revolution, an anti-Semitic saying circulated in White émigré circles: "Vysotsky's tea, Brodsky's sugar, and Trotsky's Russia." In fact, there was no place for either Wyssotzky or Brodsky in Trotsky's Russia: their property was nationalized, and the entrepreneurs themselves were forced to flee the country. However, Wyssotzky's tea can be bought now.

About the supplier of the court of His Imperial Highness

Tea spread in Russia since the 18th century, and in the next century, under Nicholas I, it became very popular in all the society. It was drunk by nobles, merchants, cabbies and even the poorest peasants.

Before Wyssotzky, for 150 years, tea came to Russia from Kyakhta. For almost a year, carts went by land from China, through the steppes of Mongolia, the Far East, Siberia, through the Ural Mountains, through the endless expanses of Russia. Snow. Rains. Snowstorms. The tea was damp. Theft. Corruption. Bring it to this official, pour it over to that official. All this affected the price and quality of the goods.

The situation changed radically after the Suez Canal was opened for shipping in 1855 and the government of Emperor Alexander II issued a permit to import tea into Russia through ports on the Black and Baltic Seas. If at the beginning of the 19th century tea accounted for 4 percent of the value of all Russian imports, then by the end of the century its share had doubled and even surpassed beverages.

Because of this, the tsarist government even feared leakage of precious metals to China. Therefore, a ban was introduced on the purchase of Chinese goods, especially tea, for silver.

However, a year before the death of Tsar Nikolai Pavlovich, in 1854, the state lifted all restrictions on tea imports. In the same year in the city of Kovno (now Kaunas, Lithuania), to the great sage of the Torah, the founder of the ethical movement "Musar" Isroel Salanter, his compatriot Kalman-Wolf Wyssotzky came to study from the town of Starye Zhagory. Prior to that, he studied for four years at the famous Volozhin yeshiva.

For a good Jewish religious education, this is not a serious period, but, apparently, the parents had enough money only for these few years. And Kalman-Wolf did not plan to go to the rabbis. After leaving the yeshiva, Wyssotzky began to trade grain in the town of Yanishki.

At that time, the tsarist government encouraged agriculture among the Jews. Wyssotzky gathered partners and received from the treasury a piece of land near Dvinsk. There they founded the village of Dubno. But it didn't work out: the soil turned out to be bad. He had to return to his native Zhagora to trade in bread. It was here that an entrepreneur at the respectable age of 30 decided to learn from the great Torah connoisseur in Kovno. Either the righteous man gave him a blessing, or he analysed the market (and perhaps both), but after staying with Israel Salanter, Wyssotzky turns his attention to the tea market.

In 1871, the first steamer from China arrived at the Odessa port, the holds of which were filled with tea. Wyssotzky began to buy cheaper tea, of higher quality. And he changed the Russian market, taking a key position in the industry.

The tea boom began in the Russian Empire. If in the 1850s the volume of tea imports amounted to 372 thousand poods (5.9 thousand tons), then in the next decade it was twice as much, and in the 1870s - 1480 thousand poods (23.7 thousand tons). In general, during the 19th century, tea consumption increased 20 times.

In 1858, Wyssotzky moved to Moscow. Jews in those days were forbidden to live there, but an exception was made for the merchants of the First Guild. This is how the firm “W. Wissotzky & Co." is one of the largest enterprises in the Russian Empire, and after the collapse of the empire, it was a well-known international company.

In 1881-1882, Jewish pogroms took place in different regions of the country. After that, Zionist circles and groups were opened everywhere in Russia, the first aliyah began (the immigration to the Holy Land).

Wyssotzky launched charitable activities, supporting national institutions in the Holy Land, in particular, he financed a school in Jaffa. The tea merchant donated a lot to the settlement of Palestine, which at that time was a province of the Ottoman Empire. Wyssotzky was also an honorary member of the Odessa committee of the "Society for the Help to Jews of Agriculture and Crafts in Syria and Palestine."

In 1885, as a member of the Hovevei Zion (Lovers of Zion) organisation, the entrepreneur travelled through the land of Israel. In the same year, Wyssotzky donated 10 thousand rubles for the creation of the Higher Jewish Academy. In general, he constantly donated to education. For example, I gave 60 thousand rubles for the construction of a craft school in Bialystok.

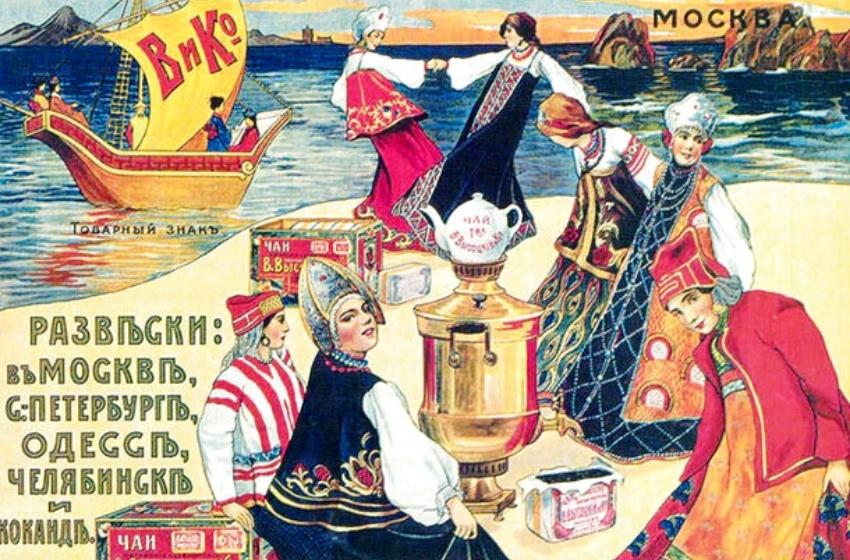

It turned out that the subjects of the Russian crown indirectly supported Zionism with every cup of tea they drank. And absolutely everything, including the imperial family. Wyssotzky received the status of "supplier of the court of His Imperial Highness Nikolai Mikhailovich." In addition, he became the supplier of the monarch of Persia - Mozafareddin Shah from the Qajar dynasty.

During the First World War, the products of "Wyssotzky and Co." were included in the army food ration.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Wyssotzky was the tea king of Russia. His company controlled 35 percent of the retail tea trade, the authorised capital of the enterprise was 10 million rubles, and the annual turnover exceeded 30 million.

Kalman-Wolf died in 1904, when his business was at its peak. He bequeathed to donate one million rubles to charity, which corresponded to the size of his share in the company (10 percent of the capital). Part of these funds - 100 thousand rubles - by the decision of the guardians in 1908 was directed to the foundation of the Institute of Technology in Haifa. Today it is the famous Technion.

Odessa

Since 1912, at 40 Kanatnaya Street, there was a Tea-packing factory of Wyssotzky. The building, painted green and decorated with floral ornaments and columns, has survived to this day. Initially, the house was built specifically for the tea-packing factory, but not for Wyssotzky, but for Smirnov, and in 1910, according to the project of engineer V. I. Kundert, reconstruction was carried out for the factory of the tea trade partnership "W. Wyssotzky and Co".

In Odessa, the tea business was very successful, because Odessa, as a large Black Sea port, accepted ships with tea cargo from India, Ceylon, and the island of Java. Warehouses for storing tea were created in different parts of the city, with their subsequent transportation to the cities of the Russian Empire. So, one of the warehouses was located at the corner of Uspenskaya and Rishelievskaya streets.

The confiscated stocks of tea from David Wyssotzky and other tea merchants were so huge that Soviet Russia did not buy tea abroad until 1923.

In 1912, the company hung tea from India, the islands of Ceylon and Java for over 9 million rubles. There were more than 300 workers at the Odessa factory in the same year. There were also factories in Moscow and other cities, as well as an international office in London. The number of employees reached 22 thousand people.

During the First World War, the products of "Wyssotzky and Co." were included in the army food ration.

The packaging of the tea was automated, and the advertisement for the tea mentioned that it was "packed without touching the hands." Tea was packed in beautifully designed cans, in which the Odessa tea factory was mentioned in the list of Wyssotzky's factories.

In the first years of Soviet government, the building was transferred to the state committee "Tsentrochai". In the 20s of the last century, the building housed the 1st state tea-packing factory and warehouses.

Wyssotzky's tea-packing factory, which received its present appearance when the old building was rebuilt by the architect V. Kundert in 1909. Photos of the factory from 1911–1914. from the collection of the Moscow State Historical Museum.

Continuation of a story

Wyssotzky had three daughters and a son, David, who inherited the company. But it was already called “D. Wissotsky, R. Gots and Co."- named after the son-in-law of the tea king Rafail Abramovich Gots. In 1914, before the First World War, the company's annual turnover reached 45 million rubles.

And then the Tsar issued a decree that increased the incomes of tea magnates by more than one and a half times: a Prohibition "dry" law was introduced in the empire. The production and sale of all types of alcoholic beverages from July 19, 1914 was banned. Tea consumption in the country just skyrocketed. In 1915, the turnover of the Wyssotzky-Gots tea company exceeded 70 million rubles.

The Wyssotzky family was associated with many famous people. Boris Pasternak wooed David Wyssotzky's daughter Ida, but was refused. The Wyssotzky salon was attended by all Moscow bohemia. The tycoon also headed the Economic Board of Jewish prayer institutions in Moscow. The tea king's grandchildren abandoned religion, carried away by socialism. Mikhail and Abram Gotsy founded the Socialist-Revolutionary Party and took up the revolution.

When the revolution came with their help, the Wyssotzkys and Gots lost their business and were forced to flee abroad. The confiscated stocks of tea from David Wyssotzky and other tea merchants were so large that Soviet Russia did not buy tea abroad until 1923.

In fact, David did not leave the business: while living in London, he arranged the packaging of tea in Warsaw and during the NEP (New Economical Policy) years smuggled it to Soviet Russia.

After the run from the Bolsheviks, David Wyssotzky opened branches of the company in the free city of Danzig, and then in other European countries. The main division of the firm was headed by Alexander Chmerling and one of Wyssotzky's descendants Solomon Seidler. His son Simon in 1936, sensing the approach of war, left for Palestine, then a British colony. The tycoon's descendants who remained in Europe were killed by the Nazis, and the company lost all European assets.

Today, from that huge company there is only a family business in Israel. Nevertheless, it controls 76 percent of the local tea market and exports products to other countries: Canada, Britain, Australia, Japan, South Korea, Hungary, Russia, Ukraine and the United States. Tea is produced in Galilee, the number of staff is about 400 people. The company is run by a 71-year-old descendant of the Wyssotzkys, Shalom Seidler. The company operates under the Wissotzky brand and, in addition to the tea market, is developing the production of olive oil and various delicacies.