This article is an extract of a report by the media Trap Aggressor

European sanctions were supposed to stop the Russian military industry, but instead, Western chemicals became its anti-corrosion armour. Without imported resins and hardeners, ships, aircraft and missile factories would quickly rust. However, the Russians have devised dozens of schemes to circumvent the sanctions, from Serbian intermediaries to Estonian subsidiaries operating near the border. The result: millions of euros worth of European chemicals are contributing to produce the very weapons used to attack Ukraine.

How anti-corrosion coatings keep the Russian shipyards and military industries afloat

When you see a tanker at sea, a warship in port, or huge tanks at an oil refinery, you are not just looking at metal – you’re looking at layers of industrial enamel. Without it, Russian cruisers, tankers, aircraft and oil depots would gradually turn into a pile of scrap metal.

Anti-corrosion paint and varnish materials (PVM) are a complex chemical industry. At the core of this technology are resins (such as epoxy, polyurethane, etc.) and hardeners, which together form a protective barrier. Simply put: the resin acts as a binding base, while the hardener triggers a reaction that transforms the liquid coating into a polymer that is resistant to water, chemicals and temperatures. Therefore, anti-corrosion coatings are a kind of chemical ‘armour’ that prolongs the life of the Russian military and economic machine. Without it, the metal surfaces would quickly degrade, especially in humid, salty or chemically aggressive environments.

This raw material is also used in the production of weapons, making them lighter, faster and more lethal. Epoxy resins are part of carbon fibre and composites. According to the Economic Security Council of Ukraine, such components are used in Russia in production of 9K720 Iskander-M missiles and strike drones, which are used in thousands of attacks against Ukrainian cities.

How Western chemical products reach Russia

High-quality paint components are difficult to manufacture. To this day, Russia is unable to produce them entirely on its own. Therefore, it mostly imports them from Europe and the United States. Following the exit of several foreign companies from the Russian market, the number of manufacturers producing industrial anti-corrosion coatings has drastically declined – especially those specialising in aviation and marine coatings (PC). Therefore, almost all of them cooperate directly or indirectly with the Russian military-industrial complex or companies under sanctions.

Despite this restrictions, Western-made goods still make their way into Russia, and manufacturers come up with ingenious schemes.

Import from Italian and US producers

The simpler method was chosen by the scientific–manufacturing company YarLI, which found two cooperative manufacturers in Italy. In 2024 alone, via a network of legal entities, the company purchased $1.8 million worth of epoxy resin from Novaresine Srl and another $1.5 million from Sir Industriale SpA. In a 2024 interview, Sir Industriale’s director Marco Bencini stated that 65% of the company’s turnover came from foreign trade and emphasized its focus on new markets in the USA and Middle East, but made no mention of operations in Russia.

When direct deals fail, YarLI turns to intermediaries. For example, it exports products via the Polish logistics firm Bildex Europe, owned by Russian entrepreneur Dmitry Kocherghin. The firm signed contracts worth $4.8 million with YarLI subsidiaries, all for the supply of epoxy resins (originating from French company Arkema and German Evonik) as well as titanium dioxide – a substance in urgent demand across Russian industry. In coatings, it provides durability to anti-corrosion layers. YarLI obtained titanium dioxide under the Ti-Pure™ brand, manufactured by U.S. corporation The Chemours Company. In response to a Trap Aggressor inquiry, the US group denied any business relations with Bildex Europe.

Over the years, YarLI has supplied paint-and-coating materials to sanctioned companies: KAMAZ (Kama Automobile Plant), Russian Railways (RZD), Severstal (Northern Steel), Tatneft, the Uralvagonzavod tank producer, the URAL auto plant, Tikhvin Carriage Works, and Izumrud (a radar equipment developer). The company employs over 600 people and reported 1.29 billion roubles in net profit in 2021. Its owner, 79-year-old Vladimir Manyerov, is among the wealthiest persons in Yaroslavl.

Russian subsidiary in Estonia

A more cunning strategy has been employed by Emlak, a company based in St. Petersburg. Its owner Mikhail Polkovnikov, together with Evgeny Tkachenko, established factory in Narva, Estonia, in 2015, marked by a ceremonial opening attended by the city’s mayor. Narva is directly across from Ivangorod in Russia, and the Estonian branch—Emlak Eesti OÜ—is less than 4 km from the Russian border. The Estonian-registered plant supplies epoxy resin to the company’s St. Petersburg headquarters. Trade volumes amount to about $1.3 million for 2023–2024.

Emlak’s customers also include the Russian Navy, Rosmorport (part of the Federal Agency for Maritime and River Transport), Gazprom Marine Bunker, and the Kronstadt Marine Plant (part of the United Shipbuilding Corporation). All of these enterprises are directly involved in the war against Ukraine.

Dutch and German groups still operating in Russia

There are also some Western firms that remain active in Russia. One such example is the Dutch company AkzoNobel. In 2007, the company opened its own plant in Orekhovo-Zuyevo, and by 2008 it had become Russia’s largest producer of powder coatings, including corrosion-resistant coatings for the construction of the Crimean Bridge.

After the start of the full-scale invasion, AkzoNobel issued a press release promising to cease cooperation with the aviation sector in Russia and to freeze investments and marketing activities. Yet neither promise was kept. For example, AkzoNobel’s Dulux brand actively advertises on Telegram. In early 2024, The Insider reported that Russia’s S7 Airlines’ 2022 report mentioned it purchases paints from AkzoNobel. Its subsidiary S7 Technics services not only S7 aircraft but also those of Aeroflot, Rossiya, Zoom Air, Ural Airlines, etc. Another company, LUXEIR, servicing yachts and aircraft, claims to use materials approved for civil aviation, including those from AkzoNobel, PPG.

Although AkzoNobel does not receive direct government contracts, its products are widely used by Russian state structures. Until mid-2024, the Russian division received part of its raw materials from Swedish and Italian branches of AkzoNobel. However, in mid 2024, AkzoNobel finally ceased supply through its foreign subsidiaries. Now, most chemical substances are imported by Russian LLC Akzo Nobel Coatings through a series of Turkish companies or via divisions of the German corporation Allnex, which also did not exit the Russian market. In response to Trap Aggressor's letter, AkzoNobel essentially distanced itself from the Russian division:

«Remaining operations are focused on our decorative-paint activities, fully localized and limited. They operate independently, without financial support from Akzo Nobel NV. We do not participate in product development or marketing. Moreover, we do not supply products to companies or individuals on the sanctions list, regardless of whether they are in Russia or abroad».

AkzoNobel assured that it strictly complies with sanctions and regularly monitors its intermediaries. However, the company could not explain how its products are reaching the Russian military or traded in Crimea, despite having been alerted to this several times.

Russian dependence on Western chemistry

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the EU introduced a series of sanctions restricting the export of chemical substances to Russia. Notably, the eighth package on October 6, 2022 banned the export of goods that could strengthen Russian industry, including certain chemicals. The twelfth package on December 18, 2023 extended this to resins, paints, varnishes, and other materials used in construction and the paint-and-coatings industry. The eleventh package, which preceded it, had already strengthened control over dual-use goods to prevent their re-export through other countries.

These restrictions have significantly complicated the operations of Western chemical companies’ subsidiaries in Russia, which had previously supplied modern technologies and quality raw materials. As a result and due to the risks of doing business in Russia, most of them decided to exit the market — though not all did. At the beginning of 2022, the paint-and-coatings market looked like this:

- 18% – Tikkurila (Finland)

- 10% – NPC YarLi, Huntsman-NMG (foreign), and Akzo Nobel (Netherlands)

- 6–8% – Jotun Paints (Norway), Kamsky Plant of Polymeric Materials, Sun Chemical, BASF Vostok (Germany)

- 4–5% – Russian Coatings, Hempel (Denmark), Lakra Synthesis, KG Stroiy Sistemy.

The largest market participant, the Finnish company Tikkurila (part of PPG Industries), announced its intention to exit Russia in July 2022 due to "inability to operate sustainably even at a minimal level." However, it completed its withdrawal only in February 2025. Norwegian Jotun, Danish Hempel, and American PPG (all under the PPG Industries umbrella) were acquired by the Russian group Litum.

In May 2024, with Vladimir Putin’s approval, one of the largest paint-and-coatings producers, Lakra Synthesis, purchased 100% of BASF East LLC, the Russian subsidiary of the German chemical group BASF.

How to neutralise Russia’s industrial camouflage

Western chemistry in Russian paint seems like a routine commercial case. But these ostensibly peaceful supplies help the Kremlin wage war: pumping oil, painting ships, repairing aircraft, launching missiles. Through complex schemes using intermediary companies, Russia continues to obtain the necessary materials supporting its military–industrial complex.

A truly effective response to Russia’s «industrial camouflage» will only come with a full sectoral ban on the export of key chemical products used for anti corrosion coatings, composites, and paints, with a stricter oversight by Western companies and governments.

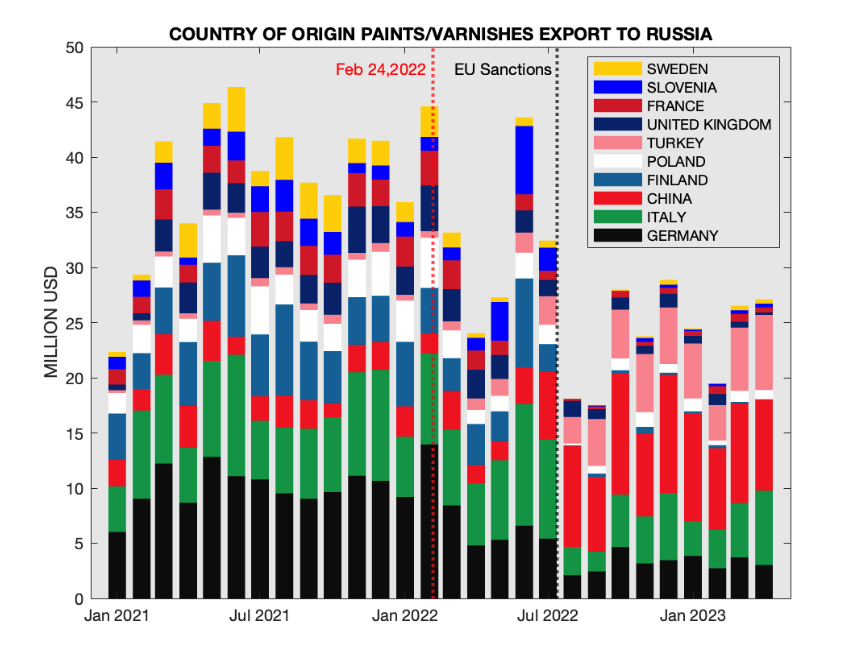

Graph: dynamics and change of key exporters after the imposition of sanctions (Source: Squeezing Putin)