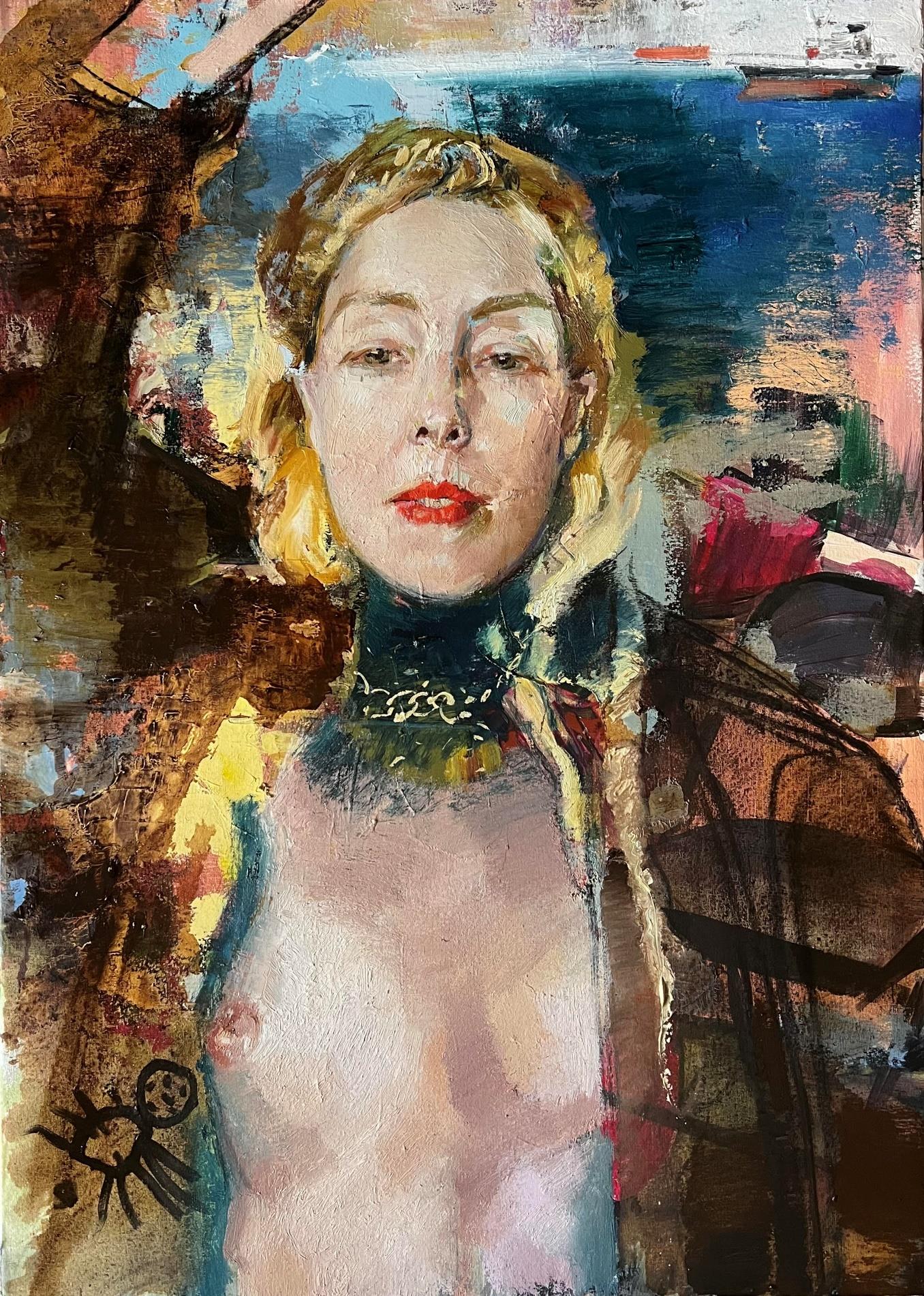

Main image: Kateryna Biletina

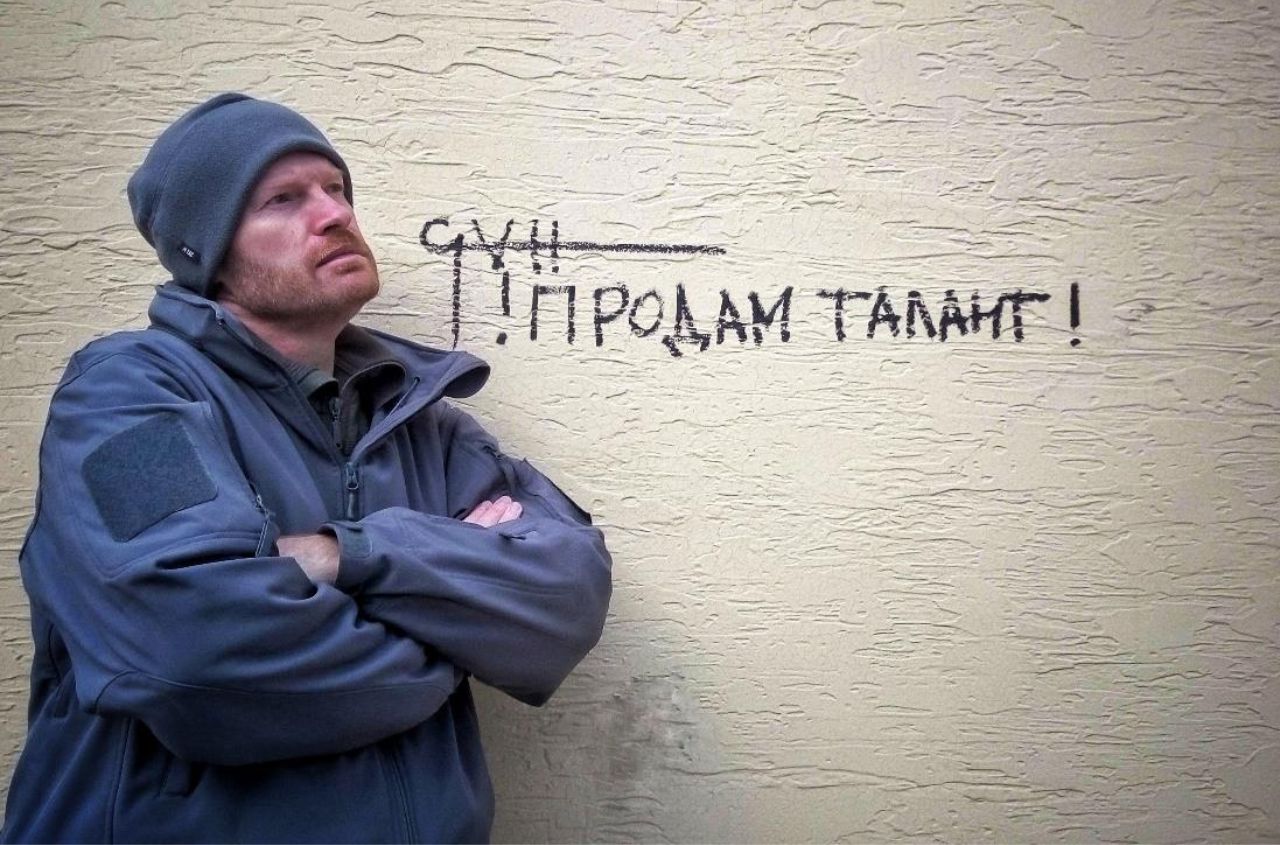

Eleventh interview through images by Andrew Sheptunov

Artist Kateryna Biletina is one of the vivid voices of contemporary Ukrainian painting. Born in Odessa, she studied at the Grekov Art College and later at the National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture in Kyiv.

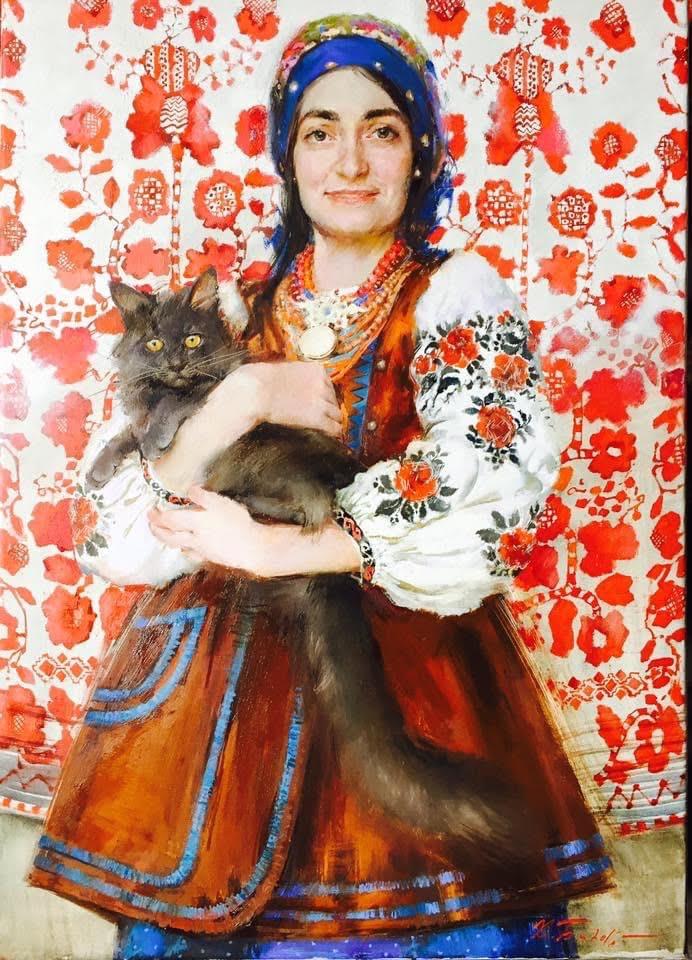

In her projects, Biletina returns to her roots: through the series Ukrainian Portrait, she creates images of people in traditional folk dress, seeking to reveal not only a face but a cultural code — a living fragment of history. Her works are held in private collections in Ukraine and abroad, while the artist herself continues to live and work in her native city.

Folk art is a unique sphere of creativity that grows outside academic institutions and within local cultural traditions. By definition, it is visual art born from folklore — often handmade, with both utilitarian and decorative purposes. Its essence lies in continuity, craftsmanship, and its deep connection to everyday life and collective memory.

Rooted in both tangible and intangible heritage, folk art embraces ceramics, textiles, wood carving, and other crafts passed down through generations. In the modern context, it has become a meeting point between tradition and contemporary art — a field where artists reinterpret ancestral motifs, infusing them with personal meaning and modern sensibility.

In Kateryna Biletina’s work, folk art is not merely an aesthetic choice but a form of dialogue — between past and present, between individuality and cultural memory. The traditional costume in her portraits becomes a symbol of identity and a tool of visual storytelling. Her paintings invite viewers to pause and see the everyday as something layered with history, beauty, and continuity.

In this new project, Biletina speaks in two languages — the language of images and the language of words. Each painting is accompanied by a brief commentary, like a quiet note left in the margins. Together they form a sequence of responses where painting becomes a way of reflection, and the written word — its gentle echo.

1. What would a “portrait of a person who remembers their roots” look like? A person in modern clothing with Ukrainian elements — a vyshyvanka, belt, or traditional jewelry, in the spirit of Ukrainian Baroque.

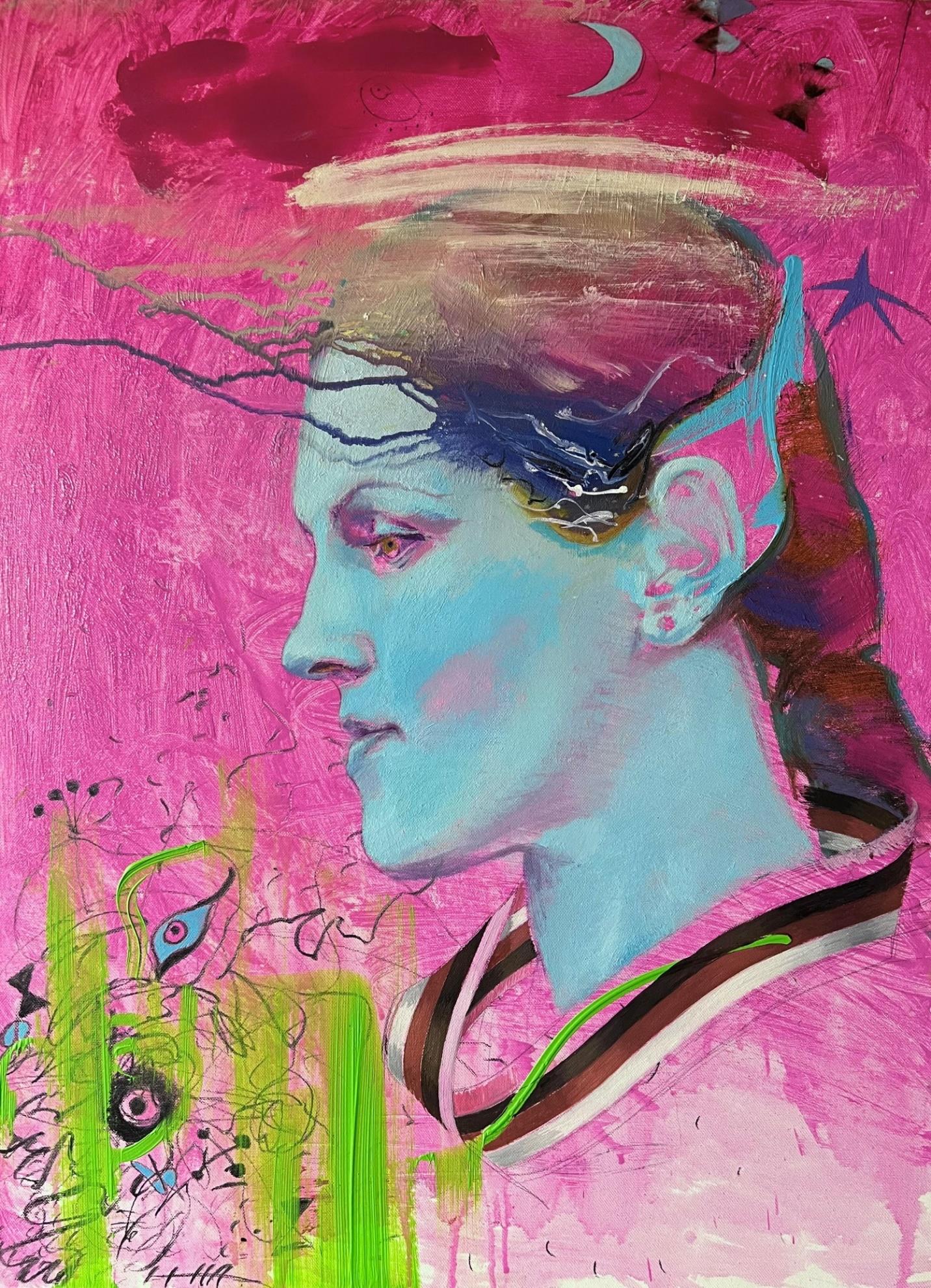

2. Would you make a “portrait of a person who does not know where they come from,” and what would their costume look like? Yes, in a surrealist manner — a collage of symbolic objects: a house-shaped hat, a night-sky coat, fish-shaped legs.

3. What would a “21st-century Ukrainian portrait” look like—without reconstruction, but with memory? A modern figure against a Ukrainian landscape, folk architecture, or symbolic details — a rushnyk or red viburnum.

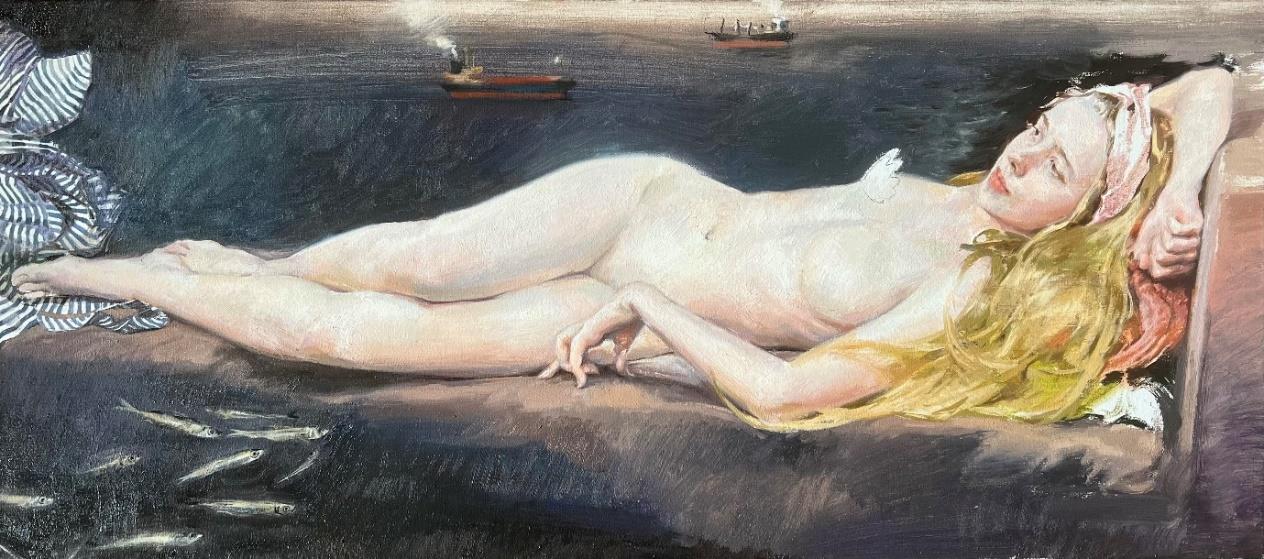

4. What background would you choose for a portrait of a person who lives near the sea? A dark monochrome — a reflection of wartime and fragile hope; as in my series Black Sea.

5. Show “love for one's native home” — without a house in the picture. Only in a person. Through a folkloric detail — a chest, porcelain, lace — symbols that awaken childhood memory.

6. A portrait without a hero: can you create a work where the costume speaks instead of the face? Yes, because clothing often reveals more than a face — taste, beliefs, and self-presentation.

7. A portrait of a person “between the city and the village” — what is the conflict in it? A tension between outer image and inner values: the city demands presentation, the village — sincerity.

8. What would a self-portrait look like where you are not an artist, but part of a tradition?

I rarely paint self-portraits, so it would be a portrait of a contemporary woman presenting herself as part of tradition.

9. If you had to paint “Family Memory” with one thing, what object or fabric would you choose? A black sarafan from the Kodyma region — a link to southern Ukraine and steppe culture. My recent self-portrait shifts from national to regional identity — a person by the sea.

10. Create an image of “unadorned beauty” — without idealization, but with warmth. True beauty lives in a face’s expression; the artist’s task is to capture that warmth with honesty.

11. If a traditional wreath were ordered from a modern beauty salon, what would it look like? It would be vulgar — artificial tropical flowers instead of authentic motifs.

12. A portrait of “a person who has just heard the word ‘folk art’ and pretends to have always known it” — what is the look in their eyes? With a slightly foolish, strained expression — “a good face for a bad game.”

Conclusion

In a world where the visual often replaces meaning, Kateryna Biletina’s art returns our gaze to the essentials — the face, the fabric, the gesture where collective memory resides.

Her characters seem to step out of forgotten canvases to remind us: the past is not static; it breathes through every stroke and every pattern of ornament.

And perhaps that is why folk art, in her hands, sounds not like nostalgia — but like a living language, speaking to us here and now.

Social media of Katerina Biletina: