One year ago, UNECE, the agency of United nations for economic cooperation and environmental policy engaged One Works, a global design and architect studio based in Milan, to develop a forward-looking, people-centred masterplan for the reconstruction of Mykolaiv, heavily shelled by Russians. One Works has been working pro bono with the mayor’s team on developing a strategic framework for the city. This will provide necessary background information on the historical, social and economic context to all those companies involved in the future works of reconstruction of the Ukrainian port city. We interviewed about this project Ana Cecilia Paez, Associate Director of One Works.

What inspired your team to take on the project of rebuilding Mykolaiv. What were the initial challenges you faced?

The UN Agency initially contacted Norman Foster Foundation to answer the request by the mayor of Kharkiv to help him out on the future planning for his city. However, One Works as well is considered by UNECE's as a centre of excellence, and later on, they contacted us with the purpose to become partner together with Norman Foster Foundation in Ukraine and realise a second project for Mykolaiv. We decided to accept the task pro bono, assigning a team within the studio that oversees the project development. We have been undertaking this since the past year as of now.

Regarding the main challenges that we faced, for sure I have to say that the first challenge was the condition of being in a conflict situation. To be very honest, when the project was presented to me, initially, I was quite afraid of what the outcome could be, considering a planning with an ongoing war. It was a unique case, in which one needs to understand how to be flexible for things to work out. Then, we met the mayor Sinkevich with his municipality’s team, at the first encounter on August 15th of 2022. And I have to say that we were very pleasantly surprised of our interface we found in the City Council’s team.

The mayor himself is a leader for the city, extremely forward thinking, opened to relationships with international partners, very much ahead in what regards digitalization. Before becoming a mayor, he was a programmer and he carried out his mandate very data-driven. So, before we came into the picture, the municipality had already invested so much in the data production and created a GIS database, that took into account everything that was in the urban fabric before the conflict began. And this for us was an initial gold mine that we dove into to understand what was the territory. Then, after that, the second thing aside from the data available was definitely the willingness that the municipality has to move forward with this project and to work together with us. They are an extremely active partner, notwithstanding the conflict around them, and that is something that we admired very much from our side in Milan. Every single week, we had at least one meeting. Some weeks even more than one. We have had two physical workshops in the studio that have been attended by them all the way from Ukraine. One was in December of last year and the other one happened in April right after the Italy-Ukraine Conference in Rome. The following week the mayor himself was in Milan with part of his press team, in order to assist to the first workshops of the next stage of development of the master plan.

Digitalization is definitely a skill all over Ukraine. How did you incorporate the historical and cultural aspects of Mykolaiv into your masterplan?

The first months of our work have been invested in setting the baseline for a preliminary framework. So it is not yet the development of the masterplan. We dove into a new territory, which is definitely also a challenge. The ongoing conflict has not allowed us to physically get there to know the city and this was a humongous challenge at the beginning, because myself I am originally from Venezuela and we are located in Italy. We have never been in Mykolaiv and had no previous background on the city. Developing a project when you cannot go and see the site is a challenge on its own. Therefore, what we did was to start analysing all of the planning documentation that the municipality had produced since 2019, considering that the latest officially approved master plan was in 2009.

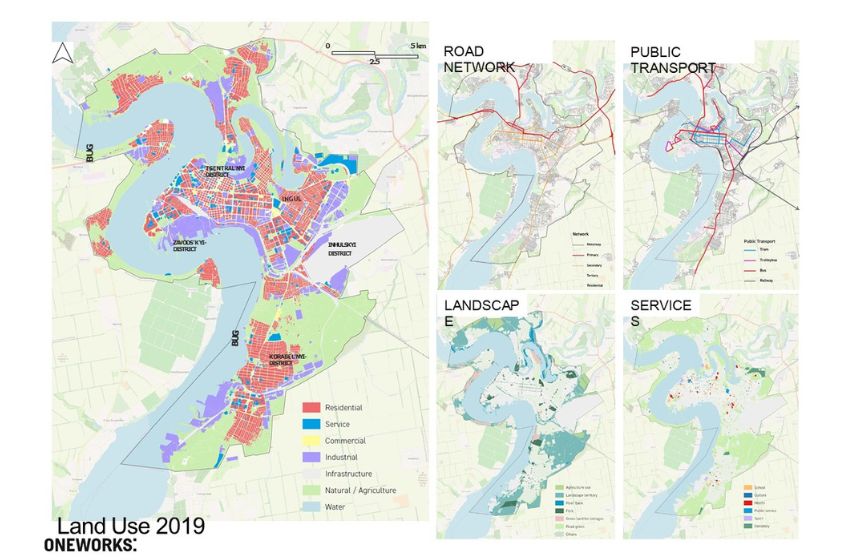

All planning documents and all relevant information provided to us by the municipality allowed us to build up a document, a very robust one, which collected all the information of what the territory was, which were the opportunities and the criticalities that were already present within the city of Mykolaiv before. So we've invested six months in studying how Mykolaiv was founded. We searched its background in terms of how the urban fabric grew over the different decades. We studied the character of the different districts in terms of architecture, as well as urban planning. We recorded all of the inheritance that was left behind from the Soviet Union. We carried out an analysis on the distribution of the land uses in the city, which allowed us to understand the strengths, the opportunities, the weaknesses and the threats of the territory before the war. The technical team that completed this baseline, is composed by over 30 different professionals from several studios and institutions. Our partners are: the academies Politecnico di Milano and LIUC Cattaneo University, GISDevio for digitisation, LAND for the development of landscape and green environments, Systematica for the public transport and the Danish group COWI for utilities.

I remember from your presentation in the conference of Rome that the mayor of Mykolaiv told you that he didn't want a city rebuilt as a copy of the previous one, but a better city. That is like redesign a city with a touch of future. How did you accomplish this task?

Actually, we are at the bare beginning of the work of the masterplan. But I think that here technology for sure plays once again an incredible role in what we are able to do today in terms of planning, especially during a war. It is widely known that in places of conflict, reconstruction processes do not work, if there's no plan. If people and governments don't have clear objectives, once the conflict finishes, everybody is swamped in with a lot of resources, which might not be channelled towards the right direction or in the right way for a successful development of the city. The mayor Sinkevich was very mindful of that and he kept on telling us that we need to use this tragedy as an opportunity to elaborate strategies with the purpose to combine the beauty of the past with the challenges of the future.

As I said, Mykolaiv is very advanced on technologies for the damage assessment. The fact that their technical team knows how to use the GIS database means that they have been able to deploy teams on the field in order to go around the city and do the damage assessment. And they've built a baseline and an interface, that we can access from Milan and that they keep on updating, interchanging the files with us. In few words, it is a sort of Google Maps, in which I can see the dots of the damages and when I click on a dot, I get a report out that is giving me all of the information about the location, the amount of square meters, what caused the damage, whether the building has suffered structural damages or only façade damages. And that allows me as an urban planner to understand what structures can be regenerated and which one needs to be demolished. For example, if a building needs to be demolished, it will generate a new void within the city area and, in that moment, we can assess whether in the previous Mykolaiv that was a residential area lacking of services.

Today, there is much talking about the mixed-use city and how to enhance service provision in shorter distances, so that citizens can move in a more sustainable way. For example, people can ride their bicycles to work, so that we reduce CO2 production. And this all has a lot to do with how we balance the land uses in the cities. So this is what the mayor meant, when he said to use the opportunity of this tragedy. Now, if I have that void in which there is no building anymore, we can insert a service that it helps all the residential area around. And we wouldn't have been able to do this, without the technologies that are present today and a savvy municipality using these tools and sharing this information with us. I think that a message that needs to come out here is that, even if everybody's talking about the use of drones and of technology to make war, we should try to go the other way around and see how technology can also help us and give us this kind of opportunities in order to build back better and make our cities in general much more resilient.

So far, all this work was finalised to show the portrait of a future city. So how long will it take to generate a final masterplan and which are the next steps?

We're putting together a Chrono programme that looks into the development of the masterplan throughout the next year. Of course, nobody knows when the conflict is going to end and the challenge for the technical team is to figure out a way in which we can make the planning tool flexible. Just to give you another example, if the war ends tomorrow, there is a lot of the Ukrainian population that is currently displaced in shelters or that hasn't been able to settle down somewhere. Therefore, that population is looking very much forward to being able to come back home. But if the war goes on for a longer period of time, it will probably happen that the population resettles somewhere else and re-entry is going to be more difficult. Since we cannot predict that, we need to provide for the municipality different scenarios of possible futures. It means a tool that they can use as a matrix or an Abacus.

What we are now thinking of is to structure our work in three different phases. An initial phase, in which we are going to lay down the scenarios for the entire city scale. During that initial phase, we are going to look at possible different population re-entry scenarios, that are then accompanied by the economic development trends of the city. Of course, according to how much population you have, then you need to calculate for them: services, housing, jobs. And with those scenarios from the modelling, we're going to overlay on them everything else, as the housing provision, services, commercial areas, park areas, leisure, etc..

Then, on a second phase, we're going to look into the development of the pilot projects. We have got five themes for five different pilot projects. One is the micro housing district. This is going to be looking into three to four blocks of residential areas and we make a project that understands how those buildings were left after the conflict. The question is what needs to be regenerated, what can instead be demolished. Then, we can insert a new volume there. This is heavily focused on residences. We are trying to understand with the municipality if there is a way to intervene, for example, within the Soviet blocs that used to be very large, in order to try to enhance quality of life. The second pilot project that we have is the innovation district, aiming at the creation of a new mixed used neighbourhood that is going to include research centres, office areas, light industries, possibly university headquarter. Then, we have a pilot project for industries and the waterfront. This is specifically related to the situation Mykolaiv, in the sense that they have one of the largest waterfronts, riverfronts of Ukraine, but it was heavily occupied by the shipbuilding and the freight industry. Through the port of Mykolaiv, 23% of grain production from Ukraine is exported. Therefore, their waterfront is heavily industrialised and when the population sees its waterfront and compares it with the waterfronts of other cities in the world, they very clearly realise that there is a lack of social accessibility to the water. They don't have leisure areas, they don't have nice waterfront structures, commercial areas that they can visit with their families during the weekend. And what they see in European and in American cities is another thing that both the municipality and the population would like to have, as well.

Since the beginning, we launched a questionnaire of about 45 questions, asking the citizens about his living condition before the conflict began. A first part was with quantitative issues, things that you can measure with numbers in answers that are quite closed. And the second part of the questionnaires instead was qualitative. How do you perceive your city, your neighbourhood, your transportation system? How do you feel that that is working? It was very clear that the first request that they had was accessibility to a riverfront, a leisure based area that they could reach and enjoy. We had over 20,000 responses to the questionnaires, a very good result, due to a convinced promotion by the municipality and it gave us real insights of what the population wanted. Another request that came out of that was a walkable city. This is another big problem for Mykolaiv because, since the city is very industrialised, there is heavy freight traffic for all of the trucks trying to reach the port area. Therefore, the city centre was not designed as a walkable area, and now we can try to enhance that back for them.

Then, the third pilot project that we have is culture and heritage. And this is also strongly related to relationships with the population. Finally, the Green lungs is a pilot project related instead to public spaces and green areas. Another thing that we realised was the heritage from the Soviet times. In fact, they have extensive green areas even between building blocks, but usually they are not served. So they're just left there as a no man's land. So we involved a technical partner that is specialised on landscape and natural environments, in order to be able to also see how we can serving better these green areas to enjoy them and use them rather than having something left there in the open.

A big challenge is how to overcome the obstacle of legislation. We need to try and make sure that the proposals can be implementable by the municipality, once we hand them over the masterplan. And that means that there are two conditions to be satisfied. One is capacity building, thanks to the pilot projects. And this is about engaging deeply with the municipality technicians, to get them aware, step by step, as we develop this and how we are doing it. They also have to learn to develop the plan in the future, because they are going to work on rebuilding the city for the decades to come. We do not want to remain the keepers of the knowledge at all. The second condition is overcoming legislation ties. There are many things regarding the legislation that we are not aware of, which could then become a problem for the municipality to get these projects implemented. Therefore, it is important to take advantage of the fact that regional and national governments right now are getting the legislations more flexible, in order to enhance fast reconstruction processes and use the experiences of both Mykolaiv and Kharkiv to be copied elsewhere. So we need the team of the municipality working with us. Their target is to identify the problems that could be raised by legislation issues. Therefore, we have got policy advisors in our international team, who can advise back on how either the legislation can be changed or bypassed. In that way, the municipality technicians have a tool to discuss with the regional and state administration. This is one of the strongholds of the pilot project approach.

What made you particularly happy to work with this project you personally? What made this project special to you, compared to many other projects of your studio?

All of us here in the Milan’s studio, we truly believe that we are doing this to help them, for the good of tomorrow. This is a pro bono project. So we haven’t done this for the money, we have done it because we believe that we can actually, together with them, rebuild better and give back a home to this population. I think this is a beautiful feeling that has spread it out throughout the studio, but also among the municipality and even the population. We perceive it when we work with them. So I think that the fact that we've been able to establish such a good international collaboration, it's an incredible thing and it's a very inspiring for all of us.

Ana Cecilia Paez, Associate Director of One Works