In the boiling August of 1812, people were falling sick in Odessa at a rate no one had witnessed before. On August 12, a female dancer in the local theater died after an illness of only thirty-six hours. Three days later, a second performer died. A third soon took ill. A few days more, and two servants and an actor were dead as well. All had the same symptoms: a mild vertigo and headache, followed by nausea and vomiting, then fatigue and dizziness, a burning thirst, and swollen, painful carbuncles in the armpits and groin. Death followed in less than six days.

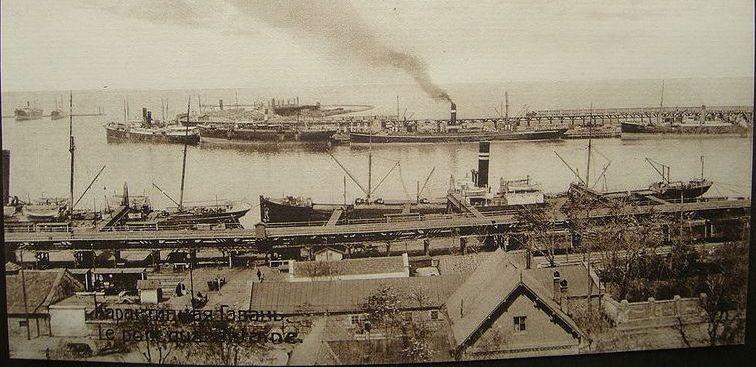

Large-scale infectious diseases such as cholera and plague were a fact of life around the Black Sea, because landscape, climate, robust trade, and variable immunity created propitious breeding grounds and transmission routes for microbes. The Black Death, a highly contagious microbial infection that wiped out a quarter or more of Europe’s population in the 1340, made its leap to the west aboard cargo ships leaving the old Genoese ports of Crimea.

The Duke of Richelieu (French Governor of Odessa and grandson of the famous Cardinal), who had just returned from a tour of Crimea, was due to take a field command in the war against Napoleon, but he wisely decided to remain in the city. He ordered an investigation into the illness. City officials soon reported that there had been a spate of suspicious deaths in the last several months, but since the dead were mainly peasants and servants, their fate had gone unremarked. Only once men and women in the public eye began to die, as those actors in the theater Richelieu himself had built, that the scale of the problem became evident. By that time, the plague had already insinuated itself deep into Odessa’s population.

The Governor called together several doctors and sought their advice. They were divided on the cause and seriousness of the illness. Some argued that it could not possibly be the plague. No sailors had been reported ill, and there was no news of the disease raging in Constantinople, which had usually been taken as a signal. But the mere suggestion that the plague might be in the city determined Richelieu to act.

On August 26 he ordered all buildings where people might gather in large numbers (churches, the commercial exchange, courts, the custom house and the theatre) to be closed. Markets were allowed to remain open. The smell of vinegar wafted through the sparsely populated bazaars, as merchants soaked their money in the liquid to prevent the disease.

As with any epidemic, information was the chief weapon. Richelieu ordered the city divided into several districts and assigned deputies to make daily reports, based on household surveys, of the progress of infection in their territory. The quarantine zone was extended far inland, to the Bug and Dniester rivers, and the length of quarantine monitored by officials: 24 days for people without baggage and 12 weeks for those with merchandise.

Notwithstanding these precautions, the number of deaths soared. District inspectors reported as many as twenty people dying each day. Physicians, racing from household to household to provide terminal care to the dying, were themselves falling victim.

At this point, Richelieu took a daring decision that probably secured Odessa’s future. He ordered the city’s borders to be sealed and established a general quarantine in all neighbourhoods. He had virtually no military forces at his disposal to enforce the quarantine. Most soldiers were at the front against Napoleon. Richelieu eventually managed to secure a detachment of five hundred Cossacks, but they were given the nearly impossible task of invigilating a city whose population had swollen to around thirty-two thousand people.

After nearly two months of general quarantine, on January 7, 1813, citizens were finally allowed to venture out of doors, although customs and quarantine barriers around the city remained in place and were never completely removed. Suspect houses were emptied or torched. Richelieu’s harsh methods, rather than stoking fear and disorder, had almost miraculously caused the plague to burn itself out. From August 1812 to January 1813, the number of people infected was 3,331, of whom only 675 recovered, a death toll of just over 10 percent of the city’s population.

Of Richelieu’s several innovations in dealing with the plague, one that mattered most to the city’s future was the egalitarianism with which the harshest restrictions on movement and public gatherings were enforced. Surprisingly for the time, Jews were subjected to the same regulations as their Christian neighbours (although infected Jews were treated in a separate surveillance facility and hospital).

In previous instances of the plague, from Provence to Catalonia and from Switzerland to the Rhineland, Jews were usually the scapegoats for outbreaks of infection. They were routinely blamed for a host of imagined transgressions, from their allegedly inadequate hygiene to grand plots aimed at weakening Christian civilization. From the fourteenth century forward, repeated attacks on Jews in western Europe, burnings, beatings, and exiles, were the main incentives for Jews to migrate to the east, from the Baltic to the Black Sea, which would eventually become the cultural epicentre of European Jewry.

In this particular epidemic, however, Richelieu managed astutely to avoid the frequent and fatal combination of plagues and pogroms, providing an early example of Odessa’s place as a refuge for an increasingly diverse community.