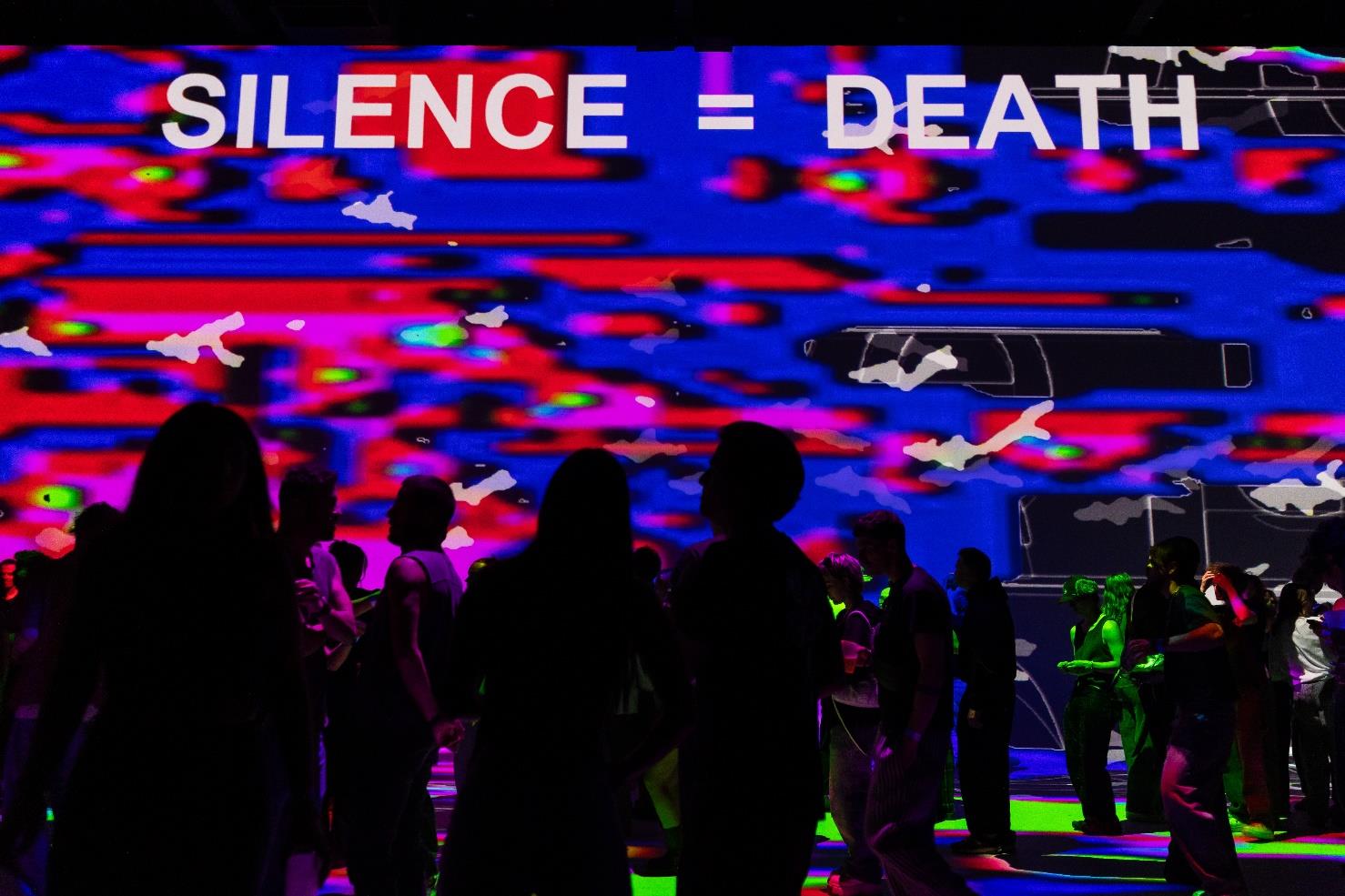

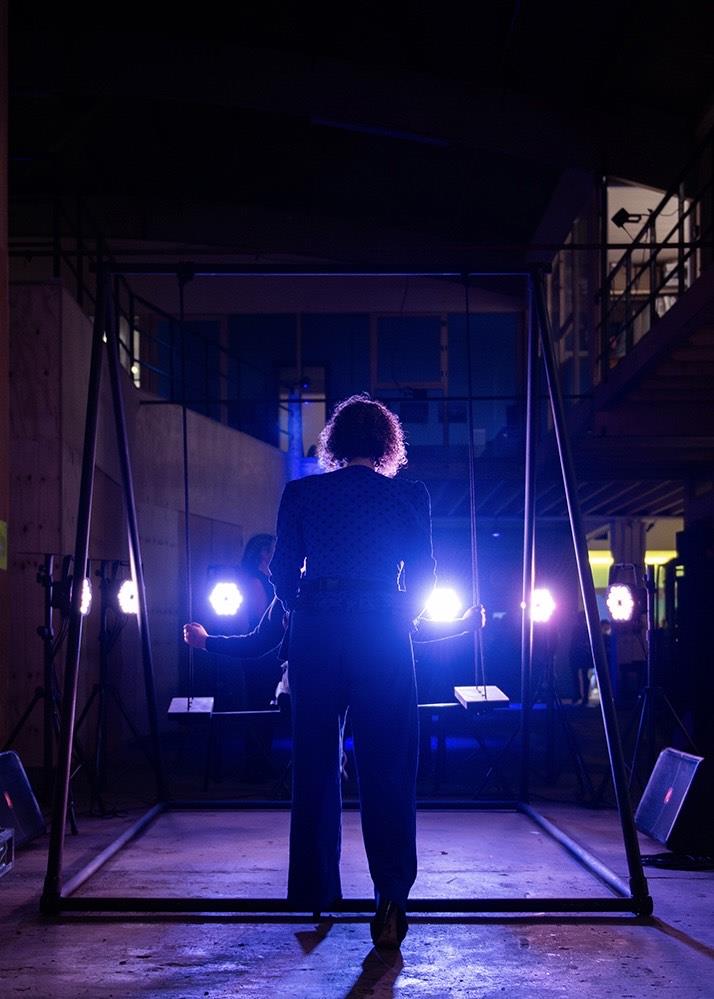

Main image: NXT Museum x Eerste Communie performance night, 2025, photo by Maarten Nauw

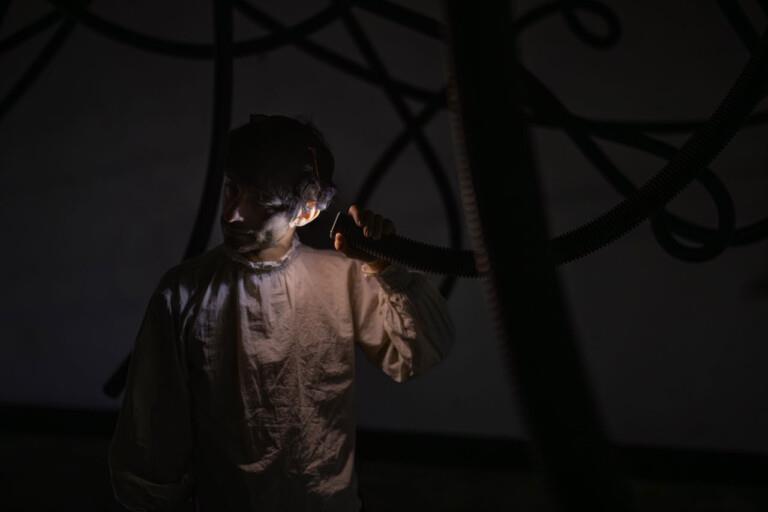

The third interview through images by Andriy Sheptunov.

We spotlight, today, Sophia Bulgakova, who was born in Odessa but now creates her work in the Netherlands. She practices in the realm of ArtScience, where scientific inquiry meets artistic expression. After beginning with sculpture studies in Kyiv, Sophia's path led her through photography and time-based media in London before culminating in The Hague's interdisciplinary ArtScience programme.

Her projects weave together projection techniques, sound, artificial intelligence, and extended reality, turning installations and performances into immersive environments where the audience is not merely an observer, but an active participant in the exploration of perception, memory, and imagination. Bulgakova’s works have been presented at major festivals and institutions in the Netherlands, Germany, China, and beyond.

Before moving on to our interview, it is worth briefly explaining the essence of ArtScience itself.

ArtScience is a contemporary current in art that merges scientific methods, advanced technologies, and conceptual thought. It draws on achievements in biotechnology, artificial intelligence, and digital media to both investigate and aesthetically reframe complex processes. At its heart lies the synthesis of science and art, where laboratory practices become part of artistic creation. Artists working in this field use cutting-edge tools to craft transdisciplinary projects that cross traditional boundaries and open new ways of perceiving the world. In doing so, scientific and technological phenomena are not only translated into artistic form but also revealed as engaging and accessible to a wider audience.

Next is an interview with the artist, where we tried to learn more about the ArtScience genre through unusual questions.

1. You often work with perception and memory. What is more important to you — how the viewer understands the work or how they feel it?

For me, the experience of the audience always comes first. I create environments where people can actively engage through their bodies — to sense, move, and immerse themselves. Through that embodied experience, they connect to the themes I’m exploring, whether it’s memory, identity, or collective rituals. Understanding may come later, but feeling and presence are the entry points.

2. Is there a difference for you between a viewer in a museum and a viewer online, in VR, or in XR space? Does your role as an artist change depending on the format?

I often try to bring XR into the museum space, working at the intersection of physical environments and immersive technologies. For me, it’s not about choosing between the

physical and the virtual, but about creating a dialogue between them. In OTHERWORLDS, for example, participants weave flowers and perform simple rituals in real space, which then merge seamlessly with virtual landscapes. This combination allows audiences to feel grounded in their bodies while stepping into another world — the physical and digital reinforcing each other rather than competing.

3. At ArtScience, projects often originate at the intersection of the laboratory and the studio. Do you feel closer to being an artist or a researcher when you start a new project?

I always begin as an artist, but my curiosity quickly pulls me into research. I read, experiment, collaborate with scientists and technologists — but it is art that gives me the freedom to cross boundaries, to mix knowledge and imagination without needing to prove a hypothesis. So I would say I am both, but my entry point is always artistic.

Sometimes I begin with a phenomenon that fascinates me — a sensory perception, a cultural ritual, or a technological behavior — and from there I shape the concept. The concept is essential, because it allows me to frame not only the audience’s experience but also the socio-political questions I want to raise. My curiosity then leads me into research: reading, experimenting, and collaborating with scientists and technologists. Art gives me the freedom to weave these strands together, so the audience can actively engage through their bodies while also becoming aware of the broader cultural or political narratives behind the work.

4. Many of your works are connected with Ukraine, traditions, and war. How do you feel when you transfer such personal and collective traumas into the art space?

It is difficult, but also deeply necessary. For me, transforming trauma into art is not only a personal act — it is a way of holding space for community and keeping awareness alive.

Works like Спомини [Spomyny], which gathers sonic memories and testimonies inside a sculptural environment of pipes, or we all woke up today from some kind of explosions, which encodes my own texts from the first year of the invasion into stereograms and dissolving analogue projections, are ways of continuing the information stream. They ensure that the conversation about the atrocities in Ukraine doesn’t fade into silence. In this way, art becomes both remembrance and resistance, connecting individual experience with a collective voice.

5. In contemporary media art, there is often talk of “technology overload”. When do you decide that there is enough technology in a project and it's time to stop?

I see technology as a medium, not necessarily the message. Besides my more critical pieces about technology itself, I use contemporary tools as media of their time — just as artists once used film or photography. For me, it’s always about highlighting the experience or amplifying the concept, not showcasing the tool. I’m fascinated by the history of technologies, so my works often move between analogue projection techniques, VR environments, AI systems, and beyond. Each medium carries its own temporal and cultural weight, and I use it only when it deepens the audience’s encounter with the work.

6. The Spomyny project is based on the sounds of memory. What sound from your childhood or past is the most powerful for you and why?

For me, it’s the voices and conversations I grew up hearing in my parents’ restaurant in Odesa. That constant stream of dialogue — fragments of stories, laughter, arguments, everyday exchanges — shaped how I experience memory. Perhaps that’s why voices and verbal narrations are so important in my work now. In projects like Spomyny, I weave together testimonies and spoken words, allowing personal and collective memories to resonate through sound.

7. What technology inspires or scares you the most right now?

Artificial Intelligence is both fascinating and troubling for me. In my project Sensitive Guidelines, I explore how generative tools reproduce propaganda, censorship, and biases — especially around war-related content from Ukraine. My approach is critical: I’m less interested in AI as a spectacle, and more in exposing the systems behind it, questioning whose stories are silenced and whose are amplified. AI inspires me as a creative medium of our time, but it also frightens me for how easily it can distort narratives and shape perception without accountability.

8. If you had to explain your art to a five-year-old, which work would you start with?

I would probably start with my earlier pieces like Inevitably Blue or YOU ARE SOURCE PROJECTION AND REFLECTION. They are fully experience-based and focus on each person’s unique perception — almost like stepping into a game where the rules are shaped by how you see, move, and respond. OTHERWORLDS also carries this playful quality: participants weave flowers, sing, or interact with virtual landscapes. All these works invite people to explore with curiosity, as if entering a world of magic where their own presence completes the artwork.

9. Your projects often exist in different countries and contexts. Have you noticed any differences in how your work is perceived in Ukraine and in Europe?

I believe art always exists in context, and perception is shaped by that context. Some of my recent works are created with an international audience in mind — to educate, to bring people closer to the Ukrainian experience of war, and to allow them to step, even briefly, into our shoes. At the same time, other pieces move in the opposite direction: they are made with Ukrainians as the ideal participants, offering ways to reconnect with traditional heritage, communal rituals, and cultural resilience. Both perspectives are important to me, because they open different pathways for empathy, memory, and healing.

10. If you had the opportunity to create a project without budget or technological constraints, what would you do first?

I’ve always dreamed of working on a large-scale film or theatre production — and that desire is still very alive in me. But I wouldn’t want to use those media in conventional ways. I imagine creating the strangest, most unexpected usage of them: a hybrid space where cinema, performance, installation, and ritual all collapse into one. A production that is not only watched but lived through, where the boundaries between stage, screen, and audience dissolve completely.

11. Rituals and traditions appear often in your work. What draws you to them in the context of media art?

Rituals are timeless technologies — they structure collective experience, shape memory, and connect us to something larger than ourselves. In my practice, I reimagine them through contemporary media to show that they are not relics of the past but living forms of knowledge. Whether through XR or analogue projections, I want audiences to feel that same sense of collective rhythm and symbolic depth.

12. Collaboration seems central to how you create. What role do collaborators play in your process?

Collaboration is essential. Many of my works are too complex to exist without other voices — sound designers, technologists, performers, communities. But beyond skills, collaboration brings perspectives that challenge me. It shifts the work away from being only my story, allowing it to become layered, collective, and more generous to the audience. I’m extremely grateful everyone I work with my long time collaborators and contributors.

13. How do you balance the personal and the political in your art?

For me they are inseparable. The personal always carries traces of the political, especially coming from Ukraine at this moment in history. When I share a personal memory, like in we all woke up today from some kind of explosions, it immediately reflects wider realities of war and displacement. And when I address political themes, I ground them in intimate details — voices, gestures, sounds — so they remain human and close.

Sophia Bulgakova stands out as one of the young voices shaping this field, bringing a unique blend of Ukrainian cultural roots and international perspectives to her work. For those who wish to delve deeper into her artistic universe — from soundscapes to immersive rituals — we recommend exploring her website (sophiabulgakova.com) and following her latest projects on social media.