In the early 20th century, the development of Ukrainian art was directly influenced by its wider European modernist context. At first, the center of the European art world was the Austro-Hungarian Secession, though it wasn’t long before Paris became the central focus. In the 1900s and 1910s, many artists headed to Paris to see the newest and most current art.

Amongst these artists was the Odessan Sonia Terk who moved to Paris in 1907 and would soon garner international acclaim as the artist and designer Sonia Delauney. Other visitors to Paris included the fellow Kyivans and classmates at the Kyiv Art School, Aleksandra Ekster and Alexander Arkhipenko. Ekster returned to Kyiv and had a signifcant influence on the development of Ukrainian Cubo-Futurism. Archipenko, on the other hand, would remain abroad, becoming a legend of international modernism, yet throughout his life he would continue to pay tribute to his connection with Ukraine.

At the end of the first decade of the 20th century, the art scene was to undergo a radical change once again. In place of modernism, impressionism, and symbolism, each with their own gentle opposition to the academic tradition and ideas of art for art’s sake, more radical artistic movements arrived. These were movements that aimed to destroy preexisting norms and to transform not only art, but the world in its entirety. This ultra-left specter of modernist thinking would be grouped together under the umbrella term “the avant-gardeâ€. However, that term was barely used in the 1910s, and the artists referred to themselves with completely different names and labels.

Thus, began the era of “isms,†and Paris was to dictate what was in fashion and what was not. It was there that, in place of Fauvism, which was the most radical artistic movement at the turn of the century, a completely new style arrived. The change in tide was marked in 1907 with Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. In the years that followed, Picasso, together with Georges Braque, would become the founder of a new artistic movement that was destined to change how we see the world forever: Cubism.

Founded in Italy, Futurism was a different revolutionary movement born under the influence of cubism and inspired by the rapid industrialization and growth of mass society. In 1909, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti wrote the futurist manifesto in which he celebrated war and the poetry of machines, while also calling for the destruction of museums, libraries, academic institutions, and all traces of culture from the past. The word futurism was hypnotic with its sense of power, dynamism, and momentum towards the future.

It was roughly at the same time that the Russian Velimir Khlebnikov would think up the local term budetlian. By the summer of 1910, artists and poets who were part of the newly formed futurist association Hylaea (Gileia, in Russian) would use the term budetlian to label themselves. At the core of this group were the brothers David and Mykola Burliuk, Velimir Khlebnikov, Aleksei Kruchenykh, Benedikt Livshits, Vasilii Kamensky and Vladimir Mayakovsky.

The family history of Davyd Burliuk, the leader of the Budetlians, is inextricably connected with Ukraine. He was born in the region around Kharkov and lived for a long time in the south of the country in the Taurida gubernia. This wasn’t far from the city of Kherson where his father worked as the manager for an estate in Chernianka. And it was precisely in this region that the Hylaea group was founded,21 named in honour of the old name of that region which dates back to the work of Herodotus.

Most of the members of this group had a tie to Ukraine, sharing an enthusiasm for the country’s history of antiquity. In St. Petersburg, the group’s raw energy triggered both interest and apprehension, and undoubtedly marked them out as decidedly different in relation to the otherwise chilly atmosphere of the northern capital. “We bear witness to a new invasion of barbarians, mighty in their talents, dreadful in their indifference. Only the future will show us if they are ‘Germans,’ or instead Huns, of which no traces will remain.†Here the poet Niklolay Gumiliov sensed the spectral energy of those from the southeastern provinces of the empire.

Any attempt to try and defne the boundaries of a “Ukrainian avant-garde†encounters the general problem of a national culture existing within a larger empire. Many artists who were originally from Ukraine are known to the world as members of the Russian avant-garde. Today researchers are actively investigating the specifcally Ukrainian components of the avant-garde movement, which were spread across the territory of the Russian empire in the second decade of the 20th century. A pioneer in this feld is Dmytro Horbachov, an art critic and a passionate advocate of the Ukrainian avant-garde since the Soviet period.

Discussions surrounding the specifc nationality of the avant-garde are methodologically ambiguous. The artists themselves were defned by a certain cosmopolitanism, and in their work they posed global questions about the limits of artistic discourse and the capability of art to exist in a state of pure non-objectivity, while at the same time retaining a utilitarian quality. However, as the history of the Ukrainian avant-garde shows, non-objective art is not itself free of ideology. While the early members of the avant-garde worked to destroy the established artistic canon, mercilessly threatening old norms and cultural codes, in fact, they were carrying out the same experiment that the Bolsheviks would soon be carrying out on a national scale. As a result, researchers of the national roots of the Ukrainian avant-garde recognize the universal agenda of those artist-revolutionaries, while also paying attention to the stylistic features, colour palette, and thematic focus of their work, which draw from the rich tradition of Ukrainian folk art. At the beginning of the 20th century, this tradition inspired a whole range of artists hailing from different positions and viewpoints.

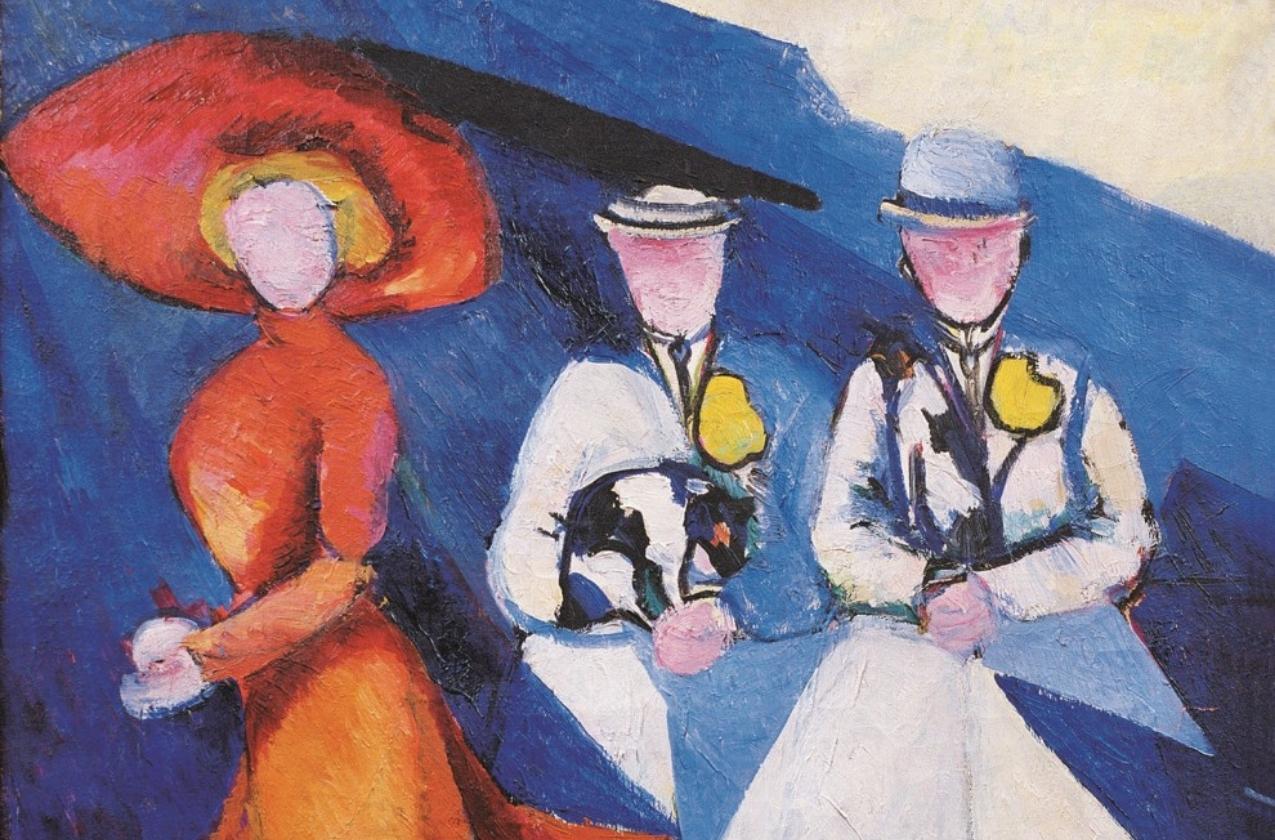

From the collection of the Natioanl Art Museum of Ukraine

During the early stages of the Ukrainian avant-garde’s development, several exhibitions were put on in Kyiv and other cities. Towards the end of 1908, the exhibition Zveno (Link) took place in Kyiv at the Musical Instrument Depot on Khreshchatyk Street. Oleksandra Ekster and Davyd Burliuk organized the exhibition and, alongside their own art, showed the work of Volodymyr Burliuk, Liudmyla Burliuk-Kuznetsova, Mikhail Larionov, and Aristarkh Lentulov. Zveno was a continuation of the exhibition Stefanos, which had opened in 1907 in Moscow.

At the opening, David Burliuk distributed copies of a manifesto entitled “The Voice of an Impressionist in Defense of Painting.†The artist declared, “The high priests of art are fleeing in their automobiles, taking their treasures with them in tightly locked suitcases. Self-satisfed bourgeoisie, your faces beam with an all-knowing joy.†While the Kyiv public did not give the exhibition the response it deserved, it all the same became a milestone event in the history of art. These were the frst steps of the future avant-garde in the entire Russian Empire.

Another milestone in the history of cubo-futurism was the Koltso (Ring) exhibition, which took place in Kyiv at the beginning of 1914. It was organized by an artist’s group of the same name, which included Ekster, though it was her classmate at the Kyiv Art School, Oleksander Bohomazov, who played the leading organizational role. Bohomazov’s own work underwent a rapid transformation during this time, evolving from a soft pointillism toward Cubo-Futurism. However, this wouldn’t have been possible without the influence of Ekster, who kept him up to date on the most recent developments in the art world from abroad.

Ekster played a huge role in the Kyiv art scene during those years. She traveled a great deal through Europe and became acquainted with Pablo Picasso and Guillaume Apollinaire in Paris and made contact with the futurists in Italy. With the priceless information she accrued, she was able to keep Kyiv up to date on the rapidly changing European art scene. The artist’s studio at 27 Fundukleivska Street became a hub for sharing new artistic ideas. Several future luminaries of the art world took part in her workshops: Vadym Meller, Anatol Petrytsky, Oleksander Khvostenko-Khvostov, and Pavel Tchelitchew. While at Ekster’s studio you could not only listen to lectures but also look at the work of her students. There was always someone of interest giving a talk, whether it was Ilya Ehrenburg, Benedikt Livshits, Yakov Tugenkhold, or Viktor Shklovsky.

In 1919, Vaslav Nijinsky’s sister Bronislava, a ballerina, choreographer, and member of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, opened the avant-garde School of Movement (École de Mouvement) in Kyiv. The school’s main purpose was to fnd a new language of choreography. It was through her contact with Ekster and her students that Nijinska arrived at an understanding of how to create a new form of ballet. The foundations of this new understanding were laid as a direct consequence of the ongoing revolution in modern painting.28 For her performances, Nijinska worked with one of the brightest lights in Ekster’s circle, Vadym Meller, and then later went on to work with Ekster herself. Before this period Ekster had already worked in a theater, making costumes for Alexander Tairov, who pioneered the concept of synthetic theater in his Moscow Chamber Theater. There she helped him stage the plays Famira Kifared (1916) and Salomé (1917).

Thus, a theatrical avant-garde was born in Ukraine, destined to become one of the brightest pages in the history of art from that period. By some miracle, sketches for these innovative performances, staged in the late 1910s and early 1920s, survived the Soviet period and today make up one of the largest remaining physical remnants of the Ukrainian avant-garde. These sketches were drawn by a range of artists such as Petrytsky, Ekster, Meller, and Khvostenko-Khvostov.

In the 1920s, the theater director Les Kurbas staged political and philosophical performances remarkable for their unique set design and for embodying the spirit of post-revolutionary Soviet Ukraine. His work is a shining example of how world-class experimental theater existed in Ukraine in the 1920s.

Alisa Lozhkina. Permanent Revolution: Art in Ukraine, the 20th to the Early 21st Century. Written by a leading Ukrainian curator and art critic, showing the history of the development of visual art practices in Ukraine, from the birth of modernism to the present day, into a cohesive narrative. Particular emphasis is given to the period since independence.

To be continued...