A forgotten story about an outstanding man, whose memory goes from the boulevards of Paris, to British clubs of Calcutta, up to the ancient temples of Nepal.

Buris (he was called only that way) was born on October 4, 1905, in the family of a nobleman Nikolai Alexandrovich Lissanevitch, a famous South Russian horse breeder, and was the youngest of four brothers. He considered his incredible life epic a direct consequence of the October Revolution. If this did not happen, he would first, according to family tradition, serve as an officer of the Russian Imperial Navy and then raise the offspring of the zealous stallion Galtimore, discharged from England, at a breeding plant in the town of Lisanevichevka.

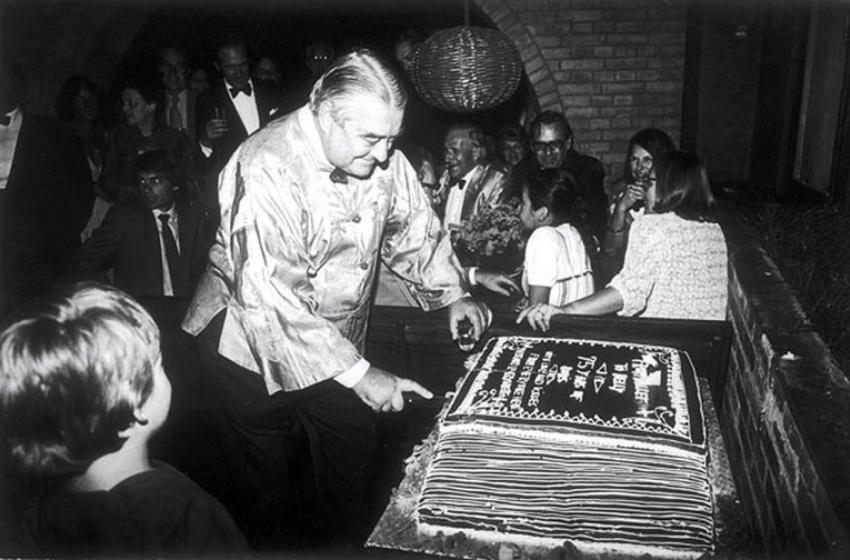

Photo from the book "Tiger for Breakfast: The Story of Boris of Kathmandu",

New York: E.P.Dutton & Co., Inc 1966

Boris was already studying at the cadet school in Odessa, when the revolutionary squabble began.

The family left the city and reached Warsaw, but then the news came that Odessa was in the hands of whites, and the Lisanevichs returned home. Soon his father disappeared, the elder brother George joined the White Guards, the second - Mikhail - died when the destroyer, on which he served as an officer, stumbled upon a German mine. Boris himself, a fifteen-year-old soldier of the Special Squadron for the Protection of the Rearguard, was wounded during a military raid somewhere between Odessa and Tuapse. Maria Alexandrovna Lissanevitch, with her two sons, Alexander and Boris, again decided to leave Odessa and try to move to Romania, but … did not have time - the Red Army entered Odessa. Later, Alexander still managed to escape from the city on a fishing scow; in the raging sea, it was picked up by an allied ship. He made it to Istanbul and then to France (in 1928, Maria Alexandrovna joined him). Boris was saved by a relative, choreographer of the Odessa Theatre, who gave him a document certifying membership in the troupe. This, in general, was not fiction - Boris began to master the basics of dance.

Well-built, hardy and artistic Boris soon performed prominent roles in the troupe's performances. Boris soon found himself in Paris. Lissanevitch worked out a contract at the Alhambra theatre, toured 65 German cities, danced at the Romantic Russian Theatre of Boris Romanov, the future choreographer of the New York Metropolitan Opera, and, finally, was accepted into the Russian Ballet troupe by Sergey Diaghilev, where he worked with phenomenal dedication and fantastic success until the death of the maestro in 1929.

I owe everything in my life to the October Revolution.

Boris Lissanevitch

He knew many ballet roles and replaced any ailing artist, played the piano perfectly, staged choreographic miniatures, and when the Diaghilev ballet ceased to exist, he became a street photographer to make a living. In those same years, Lissanevitch met and made friends with Matisse, Derain, Cocteau, Stravinsky, Lifar, Roerichs, .. however, it is impossible to list all of them.

A genuine interest in people remained in Boris throughout his life, but no less interest - and throughout his life - was aroused by his person. Generous, easily parting with money, Boris was almost chronically "stranded." His first commercial venture was the caviar trade on the French Riviera. Having earned good money, he immediately invited a cheerful group of friends to a restaurant; the evening ended at the casino along with all the funds Lissanevitch had at his disposal. He continued to dance in an enterprise, collaborated with the "Opera Monte Carlo", toured South America. In Buenos Aires, Elena Smirnova, a great ballerina from the Mariinsky, begged him to sign a permanent contract. He accepted the advance but returned to Europe to complete a number of cases.

In Paris, Boris met the young dancer Kira Shcherbacheva. Recklessly fell in love with her, returned the advance to Argentina, and got married. Together they went to London and then to Milan's La Scala.

When the British authorities refused to renew his residence permit, he was not upset and went on tour with Kira to the East. In 1933, the couple arrived in Bombay. Having worked out the numbers set by Boris in the concert hall of the famous Taj Mahal hotel (six months sold out!), They followed India's lead in conquering Burma, China, Bali, Java, Vietnam, and Ceylon.

The English-language press of the British Empire published rave reviews, and telegraphic reviews were ahead of their travel schedules. Each stage was a plot for a full-fledged adventure novel - and about Boris, by the way, more than one book will be written in French, German, Japanese and other languages; he will become the hero of reports and essays in the "Life", "Newsweek", "National Geographic".

Lissanevitch accepted the exotic East unconditionally and, absorbing it deeply, saturating the choreography and musical accompaniment with new elements.

Photo from the book "Tiger for Breakfast: The Story of Boris of Kathmandu", New York: E.P.Dutton & Co., Inc 1966

Weeks, months, years passed. Kira rebelled, and they arrived in Calcutta to return by steamer to Europe. Here they were awaited by a letter from Maria Alexandrovna, who asked her son to meet with a certain John Walford, the director of the shipping company. In conversations with a new acquaintance about this and that, the idea of ​​creating an elite club arose, and, supported by powerful sponsors, Boris plunged headlong into a new venture. So, in 1936 in Calcutta, there was a club "300".

The name had something in common with the famous London club "400". Since the figure indicated the number of permanent members, the Calcutta club, as it were, retained second place, but by decreasing the number of members, it claimed greater exclusivity. The club was housed in a marble mansion acquired by Boris, known as "Philip's Quirk". It was built for his beloved, who escaped with a simple soldier on the eve of the wedding, one of the eccentric three Armenian architects who arrived in Calcutta, in 1870, and significantly influenced its appearance. In a short time, Lissanevitch rearranged the parquet floors, redesigned the kitchen, restored the walls and ceilings, purchased luxurious furniture, and finally assembled an orchestra. Vladimir Khaletsky, a "white" officer who mastered the heights of the culinary art in France, was called to the role of the cook from Nice.

Borscht, the Ukrainian beetroot soup, was his signature dish, and he charged 10 rupees a bowl. But if someone looked impecunious, he’d give them unlimited refills with bread to go with it, which made for a full meal.

Sagar Shumsher J.B. Rana, one of Kathmandu’s best-known authors

Soon, the elite audience from all over the world rushed to Calcutta, so as not to blush when they heard:

"How come you have not been to the 300 club yet ?!"

During the Second World War, the club became a meeting place for American and British pilots who flew through the Himalayas. The events of Boris's Calcutta period would have been enough for a dozen more novels: hunting for wild elephants, tigers, and leopards, the birth of his daughter Xenia, laying air routes between hard-to-reach regions of the country, custody of fugitive Russian Old Believers, crashes and ups, trips to Hollywood, divorce from the first wife, who remained in America and opened a ballet school in Connecticut, and, finally, mad love for the blond Inger, a girl of Danish-Scottish descent, who was 20 years younger than Boris. They met in Calcutta. Inger's mother, apparently afraid of the intentions of the Russian "bear", whom everyone always suspected of espionage activities by a dozen intelligence services, sent her daughter to Copenhagen. Distances, however, were never an obstacle for Boris; he immediately rushed after, married Inger and returned with her to Nepal. In 1951, 1952 and 1954, they had three sons: Mishka, Sashka and Kolka.

Quite simply, he was the most fascinating man I ever met.

Inger Lissanevitch

Photo: Handout

In August 1954, Lissanevitch solemnly opened the Royal Hotel. The first groups of tourists and correspondents began to arrive in Nepal. Nepal looked like a mysterious state that opened its doors for the first time, one of the last blank spots on the world map.

Photo: Getty Images

According to Inger, the cheerful Boris cried only once in his life - on March 13, 1955, upon receiving the news that his closest associate in Calcutta escapades, Tribhuvan, King of Nepal, had died in a Zurich clinic. It soon became clear that these tears were not only mournful but also visionary. Almost immediately, incredible troubles fell upon Lisanevich, which no fortune teller could have predicted given Boris's high position in Nepal. At this time, he was engaged in organising the production of alcohol in Biratnagar and introducing a system of excise duties in the kingdom - all the relevant documents were signed with the government of Nepal in advance.

However, in doing so, Boris attempted to undermine the local moonshine "raksha" monopoly, which, although intended for discrete consumption by producers, went through the efforts of some influential people in Nepalese society beyond family needs and brought them considerable profits. As a result, Lissanevitch's license was taken away for the import of purified alcohol, which is necessary to launch a bottling plant in Biratnagar. One Friday evening, a platoon of police in khaki came to him and demanded the immediate payment of a huge sum as minimum compensation to the government for breach of obligations to open the plant. Stunned, Lissanevitch tried to explain that it was not he but the government that had terminated the contract. (However, in any case, he could not pay the indicated amount since the only bank in Nepal at that time was already closed until Monday.) It all ended in prison.

Lissanevitch ended up in the basement with 15 prisoners who had been put on a meager diet. However, a protest from the British ambassador soon followed, and Boris was provided with somewhat more comfortable conditions in prison. Once Inger, who visited him every day, reported that Maria Alexandrovna fell ill, who after the outbreak of the Second World War moved to her son in Calcutta, and then followed him to Nepal. She died a few days later, but the authorities did not heed Boris's request to let him go to the funeral. Days and weeks passed, and Lissanevitch's health deteriorated. He sent angry letters both to the chief of police and to higher authorities. Finally, the strange story ended: the arrived royal secretary, reproaching the fact that a civilized legal system had not yet developed in Nepal, invited Boris to write a letter of repentance to the king. Lissanevitch was furious, but at the same time, he realised that there was no other way out. They agreed on a compromise - the secretary writes, and Boris puts his signature. Lissanevitch was immediately released; the new king was received and treated kindly, who expressed the hope that Boris would not have an "unpleasant aftertaste."

The answer was simple: the official ceremony of the enthronement of Tribhuvan's son, Mahendra, was approaching, and who else could organise and hold an event at the super-level, especially since eminent guests from many parts of the globe were expected?

Life with Boris was never dull, He was very fond of animals and would keep anything, much to the dismay of some hotel guests.

Inger Lissanevitch

Later Lissanevitch laid tables for Voroshilov and Zhou Enlai, Jawaharlal Nehru, Ayub Khan and Indira Gandhi, Prince Akihito, etc. Since 1956, the moment of establishing diplomatic relations between Nepal and the Soviet Union, Boris had always been friend with the staff of the Soviet embassy. In the mid-1970s, together with Prince Vladimir Golitsyn, who visited him, he hoarsely defended Solzhenitsyn's rightness in an ideological dispute with the then Soviet ambassador Kamo Babievich Udumyan.

Boris became a legend during his lifetime. A wide variety of rumours, often mutually exclusive, circulated about his adventures and connections. No one could explain what drove him to another crazy idea, and usually several at once. No one knew, including Lissanevitch himself, whether a new venture would bring good luck or turn into a collapse.

A frantic dreamer, but who knew how to implement his plans, desperate, with obvious adventurous inclinations, but never shifting responsibility to others, this man left an excellent memory of himself.

According to eyewitnesses, the Odessa citizen more than once or twice accompanied Agatha Christie, introducing her to the outstanding monuments of Kathmandu (the capital of Nepal). In particular, with exotic wild animals within the city. Having made friends with an Odessa citizen and having learned his personal history, the Queen of detectives called Lissanevitch "an outstanding adventurer of the XX century."

Writer Viktor Klenov claims that Boris presented the British writer with a number of plots for novels. And even became the prototype of Charles Hayward from the famous novel by Agatha Christie "Crooked House".

He was a born fixer – he catered all the big events like when Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip visited in 1961. And, of course, film stars like Ingrid Bergman stayed at the Royal when they toured Nepal.

Since that day when Boris achieved this historic reversal and Nepal began to tentatively welcome visitors, tourism has become an essential core industry with consistent growth, climbing from none in 1951, to 6,000 arrivals in 1962 and 1.2 million in 2020.

In 1970, Lissanevitch closed the Royal Hotel. He later opened a new five-star hotel, Yak & Yeti, on credit from the World Bank. However, over time, he withdraws from the project without sharing the views of partners. He opened a chain of restaurants. Having started a lucrative tourism industry in Nepal, Lissanevitch himself did not get rich. He was not a good businessman; he did not chase after profits.

In general, life is a game. The only thing that matters is how many people you made happy.

Boris Lissanevitch

Boris died on October 20, 1985 and is buried among the centuries-old deodars in the deserted cemetery of the British Embassy in Kathmandu,; the key to the cemetery gate is kept by the officer on duty at the embassy. His wife Inger died in 2013. His son Michael lives in India, Nikolay lives in Copenhagen.

The 5-star Yak & Yet Hotel is still open today. In the restaurant, you can order Borsch and Chicken Kyiv.

Until recently, nothing was known about Boris Lissanevitch in Ukraine. Through the Odessa alpinists who visited Kathmandu, it became known about him in his hometown. The documentary narration of the French ethnologist and explorer Michel Peissel "Tiger for Breakfast" invariably serves as the basis for all publications about Lissanevitch.