Today, few people know her name outside the narrow circle of art historians and curators of museums and art galleries. But Edith Halpert's contributions to collecting and building the reputation of American fine arts is huge. Edith Halpert was a New York City pioneer selling American contemporary art and American folk art.

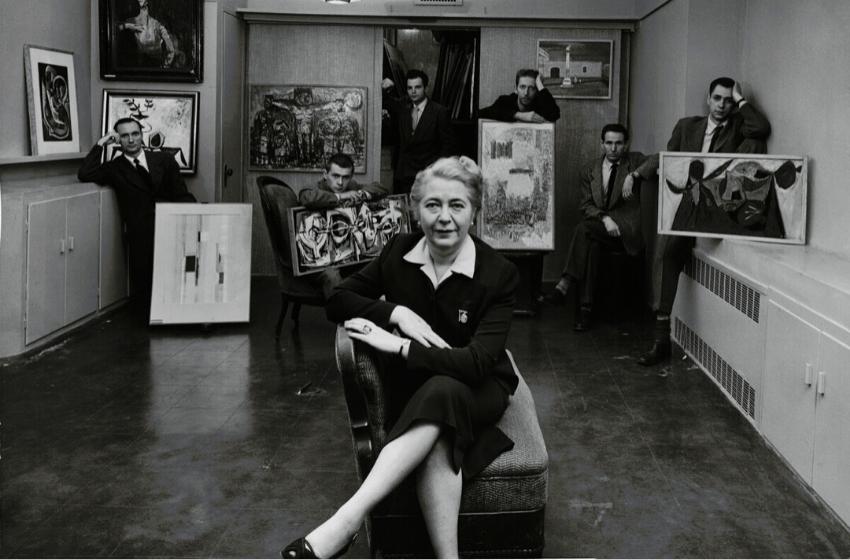

Cover photo: Edith Halpert at the Downtown Gallery, wearing the 13 watch brooch and ring designed for her by Charles Sheeler, in a photograph for Life magazine in 1952. She is with some of the new American artists she was promoting that year: Charles Oscar, Robert Knipschild, Jonah Kinigstein, Wallace Reiss, Carroll Cloar, and Herbert Katzman. Photo © Estate of Louis Faurer. Courtesy of the Jewish Museum.

Edith Halpert or Edith Gregor Halpert (née Edith Gregorievna Fivusiovich) was born on April 25, 1900, in the family of Gregor and Francis Luk Fivusiovich in Odessa. She had a sister, Sonya, who was five years older. Shortly after the fatal pogroms of October 1905, Edith immigrated to New York in 1906 with her mother and sister (her father died in 1904 of tuberculosis). At this time, the surname changed to Faivisovich.

They originally settled on the west side of Harlem, then a predominantly Jewish immigrant area, and Edith attended Wadley Progressive Girls' High School. At the age of 14, she Americanised her name to Edith Georgina Fein and began her career as an artist.

To support herself and her mother, Edith quickly changed a number of positions and became a very successful businesswoman. At 16, she worked in Bloomingdale's department store, first as a comptometer operator and then as an illustrator in the advertising department. She then worked at Macy's overseas office, and later became Advertising Manager at Stern Brothers, and then worked as an efficiency expert for a garment manufactory.

She studied drawing with Leon Kroll and Ivan Olinsky at the National Academy of Design and drawing live with George Bridgman at the Art Students League. Edith was able to enter the National Academy of Design at such a young age because she convinced her teachers that she was actually sixteen. She was also a member of the Whitney Studio Club and the John Weichel Folk Art Guild, a radical artists' cooperative for which she served as treasurer.

There she met her future husband Samuel Halpert. He was twice as old as Edith and is quite famous among artists and art connoisseurs. In 1913, he took part in the Armory Show milestone. The couple remained in New York City, where Samuel continued to paint while Halpert worked to support them.

In the 1920s and 1930s, marriage was still a popular goal among young women. Although many young women were employed, most of them stopped working after marriage. However, Halpert continued to work to support her household while Samuel stayed home to paint. Despite her youth, she became a consultant and then a member of the board of directors of a large investment bank.

In 1925, they lived at the Maison Watteau in Montparnasse the most vibrant artist community in Paris. While staying in France, Halpert noticed that French artists had more opportunities to sell and display art than their American counterparts.

The following summer, the Halperts stayed at an artists' colony founded by Hamilton Easter Field in Ogunquit, Maine. They rented a cottage from Robert Laurent and chatted with other American artists who lived there that summer: Stephen Hirsch, Bernard Carfiol, Walt Kuhn, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Katherine Schmidt, Niles Spencer, Marguerite and William Zorach.

Flush from bonuses earned in the bank, she opened the Downtown Gallery on 13th Street in Greenwich Village, where she began to exhibit the work of American artists. She strove to attract the attention of the cultural public to American art in those years when the European avant-garde was undividedly dominant in the world. She became one of the world's first women art dealers. Artists supported by Halpert, most notably Stuart Davis, Georgia O'Keeffe, Ben Shan, Charles Sheeler, and Yasuo Kuniyoshi, have become classics of American modernism over time.

The Downtown Gallery has no prejudice for any one school. Its selection is driven by quality — by what is enduring — not by what is in vogue.

The early brochures of The Downtown Gallery

In its original location, the gallery served as a place where artists (many of whom lived and worked in the neighbourhood), collectors, and aficionados met in the evenings for coffee, conversation, and sometimes lectures or other programmes.

A well-educated expert with impeccable taste and the ability to persuade the interlocutor, Halpert became a mentor and inspiration for a whole galaxy of American art collectors. Among them is Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, a philanthropist and feminist, a member of the powerful family who founded the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Her circle also included Duncan Phillips, founder of the collection of the same name in metropolitan Washington, William Lane, chief patron of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and Electra Heywemeyer Webb, collector and founder of the Shelbourne Museum in Vermont.

Halpert set herself a very ambitious task: to make contemporary American art accessible not only to wealthy collectors, but also to the middle class. To this end, she sold many works at reasonable prices available to the general public. In addition, she was actually the first to introduce the principle of installments in payments for purchased works of art.

In 1946, just after the end of World War II, the US government established a programme to promote American art abroad. A mobile collection of 152 works was created, of which about a quarter was purchased from the Downtown Gallery. According to the initiators of the project, the exhibitions sent to the USSR and the countries of Eastern Europe were supposed to help spread democratic values ​​and ideals of freedom.

However, a barrage of criticism from conservative hawks, including Senator Joseph McCarthy, prompted the US administration to hastily cancel the programme. Her critics argued that the selection of works was overly radical and tendentious and allegedly contributes to the growth of anti-American and pro-communist sentiments. The collection assembled for the project was sold out.

Halpert did not hide her disappointment.

Any nation should cherish its art. If Congress controls what we paint, then freedom of speech and individual expression will become impossible and communism will triumph.

Edith Halpert

In 1959, Halpert was invited to be the art curator of the American National Exhibition in Moscow, which was a manifestation of President Eisenhower's policy of forging cultural ties with the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War. Once again, conservatives in Congress attacked the works brought to Moscow as "subversive." At the same time, Halpert skillfully used these attacks to draw attention to the exhibition, insisting that freedom of artistic expression and variety of styles are the defining features of US national art. "Welcome Home" by artist Jack Levin has become one of the most discussed and criticized paintings brought to Moscow.

Ironically, Levin's criticized painting has become an unexpected symbol of American democracy in Moscow. The show's organiser, the US Information Agency (USIA), used it as an effective propaganda argument, and Halpert herself was awarded the USIA Certificate of Honour for "Outstanding Service."

Halpert kept working until her death in 1970, after which the gallery quickly shuttered because she hadn’t designated a business heir and didn’t have any descendants. A few years later, her personal art collection—around 400 works by American modernists she’d either been gifted or bought herself over the years—was sold at auction and dispersed.

She did not follow in the footsteps of others; she did not take the easy way of promoting and selling European art where the path was clear and well-trodden. She set out to promote American art because she believed in it and realised that if this country was ever to have an American art, it had to come out of American artists. American art owes her a great debt.

William Zorach, one of Halpert’s Downtown Gallery artists