The Russian leadership could be mistaken in the abilities of the Ukrainian army. As the US intelligence community reports, the occupiers will continue to face more challenges.

Russia’s unprovoked war of aggression against Ukraine is a tectonic event that is reshaping Russia’s relationships with the West and China, and more broadly in ways that are unfolding and remain highly uncertain. Escalation of the conflict to a military confrontation between Russia and the West carries the greater risk, which the world has not faced in decades.

Moscow will remain a formidable and less predictable challenge to the United States in key areas during the next decade but still will face a range of constraints. Russia will continue to pursue its interests in competitive and sometimes confrontational and provocative ways, including by using military force as it has against Ukraine and pressing to dominate other countries in the post–Soviet space to varying extents.

- Russia probably does not want a direct military conflict with U.S. and NATO forces, but there is potential for that to occur. Russian leaders thus far have avoided taking actions that would broaden the Ukraine conflict beyond Ukraine’s borders, but the risk for escalation remains significant.

- There is real potential for Russia’s military failures in the war to hurt Russian President Vladimir Putin’s domestic standing and thereby trigger additional escalatory actions by Russia in an effort to win back public support. Heightened claims that the United States is using Ukraine as a proxy to weaken Russia, and that Ukraine’s military successes are only a result of U.S. and NATO intervention could presage further Russian escalation. Russia’s officials have long believed that the United States is trying to undermine Russia, weaken Putin, and install Western-friendly regimes in the post–Soviet states and elsewhere, which they conclude gives Russia leeway to escalate or widen the war if it chooses.

Moscow will continue to employ an array of tools to advance what it sees as its own interests and try to undermine the interests of the United States and its allies. These are likely to be military, security, malign influence, cyber, and intelligence tools, with Russia’s economic and energy leverage probably a declining asset. We expect Moscow to insert itself into crises when it sees its interests at stake, the anticipated costs of action are low, it sees an opportunity to capitalize on a power vacuum, or, as in the case of its use of force in Ukraine, it perceives an existential threat in its neighborhood that could destabilize Putin’s rule and endanger Russian national security. Russia probably will continue to maintain its global military, intelligence, security, commercial, and energy footprint, although possibly in a reduced role, and build partnerships aimed at undermining U.S. influence and boosting its own.

- In the Middle East and North Africa, Moscow will continue to use its involvement and the activities of the private security company Vagner in the Central African Republic, Libya, Mali, and Syria to increase its influence; try to undercut U.S. leadership; present itself as an indispensable mediator and security partner; and gain military access rights and economic opportunities. Moscow’s ties to Tehran probably will improve politically and economically as both countries seek ways to circumvent sanctions, and advance closer bilateral economic and defense cooperation.

- In the Western Hemisphere, Moscow will seek to maintain its influence by continuing its diplomatic overtures and economic engagements mostly with the countries that it sees as key players or close partners, including Argentina, Brazil, Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela.

- In the post–Soviet states, Moscow is less capable of intervening in Belarus, Central Asia, and the South Caucasus than it was in 2020 in Belarus and in 2022 in Kazakhstan––in both cases to prevent expressions of popular dissatisfaction with the government from leading to regime change. Russia’s deployment of much of its ground forces and associated security personnel to Ukraine this past year probably has reduced the likelihood of Russian military intervention in other post–Soviet states.

- China and Russia will maintain their strategic ties driven by their shared threat perceptions of the United States, which create potential threats in areas such as security collaboration, specifically arms sales and joint exercises, and diplomacy, where each country has used its veto power on the UN Security Council against U.S. interests.

Russia will continue to use energy as a foreign policy tool to try to coerce cooperation and weaken Western unity on Ukraine, although sanctions resulting from the war are reshaping Russian energy relationships in both predictable and unpredictable ways. Russia’s state-owned exporter Gazprom cut off gas to a number of European countries after they supported sanctions on Russia, contributing to soaring natural gas prices.

- Likewise, Russia has used food as a weapon by blocking or seizing Ukrainian ports, destroying grain infrastructure, occupying large swaths of agricultural land thereby disrupting the yields and displacing workers, and stealing grain for eventual export. These actions exacerbated global food shortages and price increases.

Russia has used its capabilities in COVID-19 vaccine development and the nuclear power export industry as foreign policy tools. Russia plays upon corruption in other countries to help advance its foreign policy goals and buy influence. However, widespread corruption within Russia itself represents a long-term domestic vulnerability as well as a drag on Russia’s economic performance and ability to attract investment.

- Russia has used corruption to help develop networks of patronage in countries, including in Belarus and Ukraine, to try to influence decisionmaking and help carry out Russia’s foreign policy objectives.

- Russians regularly identify corruption as one of the country’s biggest problems, which has been a recurrent cause of public protests and a key theme of opposition figure Aleksey Navalnyy, who remains imprisoned.

- Even if international sanctions were eased or lifted, Russia probably would need to reduce corruption and state control of the economy, and improve the rule of law, to attract investment and expand economic growth.

Russia’s so-called special military operation against Ukraine has not yielded the outcome that Putin had expected. After its initial large-scale invasion of Ukraine on three fronts on 24 February 2022, Russia abandoned its efforts to capture Kyiv, withdrew from much of northern Ukraine, and focused on the Donbas region and other parts of southern Ukraine.

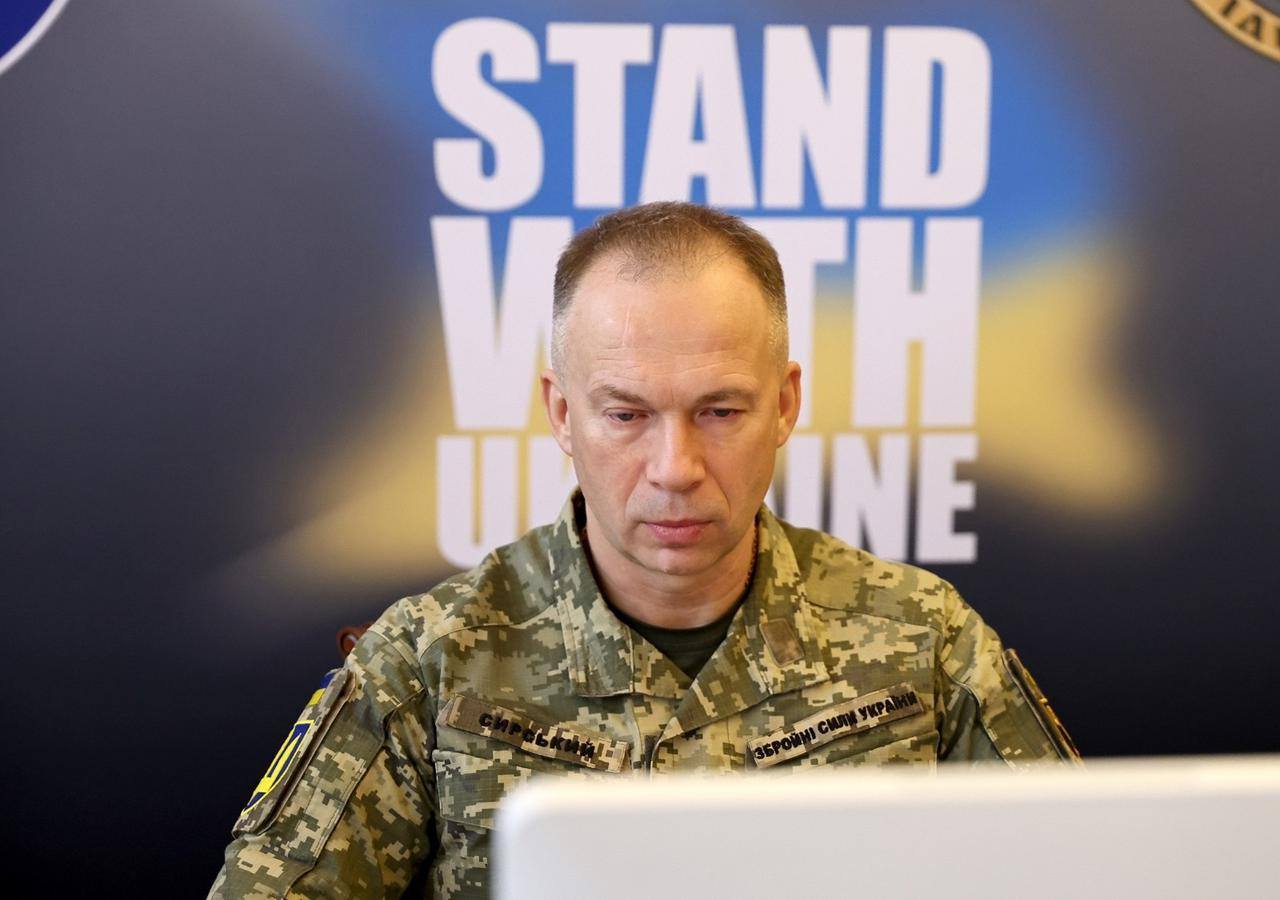

- Putin probably miscalculated the ability of the Ukrainian Armed Forces and the degree to which it would have some success on the battlefield. The Russian military has and will continue to face issues of attrition, personnel shortages, and morale challenges that have left its forces vulnerable to Ukrainian counterattacks. Putin’s announcement of a partial mobilization of mostly untrained and unprepared [ 14 ] reservists will alleviate personnel shortage in the near term, but risks undermining Russian domestic support for the conflict.

- The full effects of Russian partial mobilization will only begin to be felt into the spring and summer. Although Russian forces continue to concentrate on the Donbas, they probably will not be able to take all of it in 2023.

- Evidence of atrocities committed by Russian forces against Ukrainian military personnel and civilians will continue to emerge as Ukrainian forces retake territory.