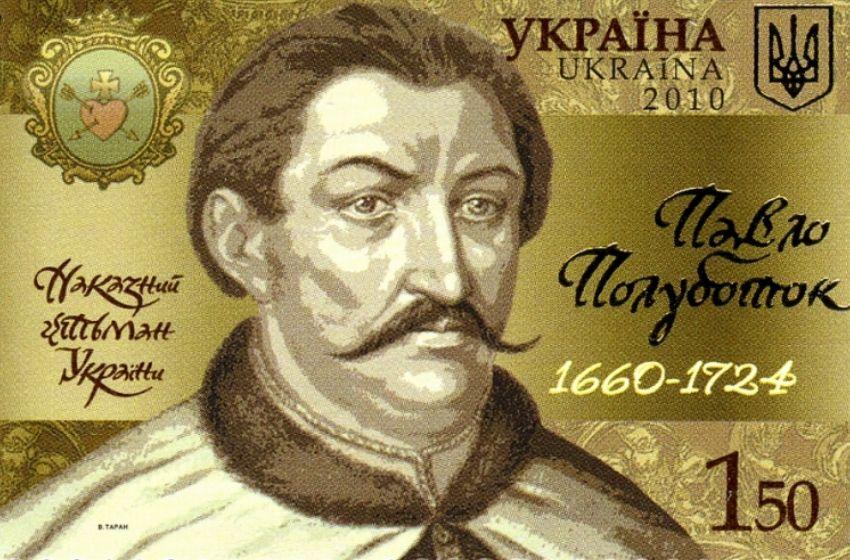

This is the story of the Hetman (Cossack leader) Pavlo Polubotok, who deposited a large amount of gold into an English bank in 1723, before being imprisoned by the Tsar Peter the Great. This legend is also called: the Gold of Polubotok.

In 1723, the Cossack Pavlo Polubotok, Hetman of Left-bank Ukraine (East of the Dnieper River), dispatched his son Iakiv and three companions to the northern port of Arkhangelsk. From there they had to sail to London on a mission of the utmost secrecy. The Cossacks carried one (or two) wooden barrel filled to brimming with between 200,000 and 1,000,000 gold rubles, to be deposited with an English bank. Unfortunately, the precise detail of the bank (Bank of England, or Lloyd’s Bank, or perhaps the East India Company Bank) have been lost to history.

Polubotok sent his gold to London because he knew he was going to be arrested by the Tsar Peter I. The Hetman had long been a staunch defender of the principles of Ukrainian autonomy, as defined by the Treaty of Pereyaslav of 1654, and had thereby incurred the first Russian emperor’s wrath. The Count Alexander Rumyantsev was dispatched to investigate the Cossack leader for “conspiracy to promote the autonomy of Ukraine,†a capital offense, and Polubotok was convicted.

In November 1723, Polubotok had been inprisoned in Saint Petersburg’s Peter and Paul Fortress, and within a year he was dead, probably starved or smothered by his captors. But, his rubles were quite safe in England, under 7.5% annual interest. Polubotok had instructed the depositors that the gold represented a bequest to the Ukrainian people, albeit one that would not vest immediately. Only upon the attainment of a “free Ukraine†would the bullion be distributed with these quotas: 20% to his heirs, and 80% to the Ukrainian people as a whole.

Russian, Soviet and Ukrainian investigations and recovery attempts

In 1907, the story first became widely known when it was published in the Russian journal New Time by Professor Alexander Rubets. In 1908, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia ordered an investigation by the Russian Consulate in London. Specifically, their unclaimed deposits at the Bank of England over the previous 200 years were controlled, and the alleged amount of Polubotok's fortune was not found.

In 1922, Ostap Poluboto from São Paulo (Brazil), a relative of the famous Cossack, met up with the Ukrainian Soviet Consul, Yuri Kotsubinsky, in Vienna and showed him a copy of the 200-year-old document attesting to his legacy. Kotsubynsky approached Grygory Petrovsky, the Head of the Ukrainian Central Committee and of the All-Ukrainian Revolutionary Committee, with a plan for the recovery of the fortune.

In July 1922, a meeting took place between Ostap Polubotok, Robert Mitchell, from the Bank of England, and the Consul Peter (Kotsubynsky was ill) in Maria-Esensdorf, outside of Vienna. The matter however came to an end with the removal and repression of both Petrovsky and Kotsubynsky during a purge.

In January 1960, the United States of Dwight Eisenhower proclaimed the Ukraine’s Day. The Soviet KGB reported that England had given money to support this propagandist action and that the money had come from the Polubotok’s bank account. The matter came to the attention of Nikita Khrushchev, who ordered an investigation to recover the money. They set up a commission, which included two historians: Olena Kompan, and Olena Apanovych. In January 1968, Olena Apanovych published her findings in a paper for the Presidium of Communist Party. She was later asked not to discuss this "State secret".

In the chaotic time of the Soviet Union's collapse, the story again attracted public attention. In May 1990, the Ukrainian poet Volodymyr Tsybulko instigated a spirit of “gold rushâ€, announcing that if the gold were returned, it would amount to 38 kilograms for each one of the 52 million citizens of independent Ukraine. This astronomical figure, was calculated on the basis of interest over 270 years. Thereafter, Tsybulko confessed that his speech in 1990 was merely propagandistic.

The heated interest in the lost treasury coincided with a visit to Kiev on June 9, 1990 of British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. In that time, the Ukrainian legislator Roman Ivanychuk announced with levity that the Bank of England would soon be owing sixteen trillion pounds sterling to the future Ukrainian Republic. “This was not a legend,†the Ukrainian ambassador to the United Nations, Gennadiy Udovenko, confidently announced at a press conference held in Geneva. The Ukrainian parliament created a special committee headed by Petro Tronko, Vice Prime Minister of Ukraine, who visited London. The gold, however, was not found.

While rumours of Polubotok’s gold had been surfacing regularly since around 1860, and had thoroughly been investigated by folklorist Alexander Rubets in 1907, no supporting evidence had ever been found. Some Ukrainians held out hope that evidence could still be found buried in Soviet archives, while others worried that most ancient bank records had been set ablaze during Stalin’s crack down on the monasteries.

In any case, it is sure that this story will survive as a nice and emblematic legend within Ukrainian history.