By Ihnatyev Stanislav, Doctor of Technical Sciences, Professor at the National University "Poltava Polytechnic named after Yuri Kondratyuk," Head of the Department of Scientific and Technical Supervision for the Operation and Development of UGS at the branch "Institute of Gas Transport" of JSC "Ukrtransgaz," Honorary Professor of the European University of Continuing Education (Slovak Republic), Associated Expert at the Ukrainian Institute for the Future.

On February 3, U.S. President Donald Trump stated that he wants to reach an agreement with Ukraine for providing assistance in exchange for guarantees of access to rare earth metals. Currently, there are active discussions about the U.S. demand for Ukrainian subsoil resources, estimated at $300 billion. I believe that this proposal from the U.S. is a unique opportunity for Ukraine to effectively develop its subsoil, create new jobs, fill the state budget, and promote the development of related businesses that add value to raw materials. However, I sincerely hope that we will enter into an adequate production sharing agreement for the majority of our deposits and agree on the localization of a large percentage of related extraction companies and technologies in Ukraine. What are production sharing agreements in subsoil use, what successful cases exist, and what are the prospects for the country? Let’s explore these questions in this publication.

What is a production sharing agreement?

A production sharing agreement (PSA) is a special type of contract for establishing a joint venture. Typically, a PSA is an agreement concerning the distribution of natural resources, concluded between a foreign mining company (contractor) and a state-owned enterprise (state side), which authorizes the contractor to conduct exploration and exploitation within a specified area (contractual territory) in accordance with the terms of the agreement.

The essence of a production sharing agreement is that one party (the state) entrusts another party (the investor) with conducting exploration, development, and extraction of minerals in a designated area (or areas) of subsoil, and carrying out related activities under the agreement. The investor is obliged to perform the assigned tasks at their own expense and risk, with subsequent reimbursement of costs and compensation (remuneration) in the form of a share of the profitable product. The parties to the agreement are the investor and the government of the state or a local authority, where the respective subsoil area is located. Multiple investors may participate in the agreement, provided they share responsibility for the obligations stipulated in the agreement. In its legal nature, the production sharing agreement is an investment contract of a complex nature that safeguards both civil (private) and governmental (public) relations.

Although the concept of production sharing was first used in Bolivia in the early 1950s, the first modern production sharing agreement was signed in August 1966 in Indonesia.

Successful Case of a Production Sharing Agreement: Tengizchevroil

A close example of a production sharing agreement in practice is the Tengiz field in the Republic of Kazakhstan and the joint venture Tengizchevroil, which has been a key budget-forming enterprise for Kazakhstan for nearly 30 years. It has transformed into a world-class petrochemical cluster and generated billions of dollars in the development of related Kazakhstani businesses.

The oil reserves of the Tengiz and Korolev fields, developed under the production sharing agreement, total 1.4 billion tons (11.5 billion barrels). The Tengiz field is the deepest super-giant oil field in the world, with the upper oil-bearing reservoir located at a depth of about 4,000 meters. The Tengiz reservoir stretches 21 kilometers (13 miles) in length and 20 kilometers (12 miles) in width, and the thickness of the oil-bearing layer is 1.6 kilometers.

The production sharing agreement for Tengizchevroil is shared by the following participants: • The state company KazMunayGas – 20%. • The multinational company Chevron – 50%. • The subsidiary of ExxonMobil Corporation, ExxonMobil Kazakhstan – 25%. • The Russian private oil company Lukoil – 5%.

Direct payments to the state budget of the Republic of Kazakhstan in 2024 amounted to $11 billion USD per year, and since the start of the production sharing agreement (signed in 1993), these payments have totaled $201 billion USD.

Production Sharing Agreement – The Ukrainian Variant

The text of the production sharing agreement (PSA) between Ukraine and the Shell corporation has been actively discussed in the highest expert circles. Experts agree that the PSA (УРП) has several advantages compared to special permits for subsoil use.

Firstly, PSAs have a longer duration—50 years, compared to five to seven years for special permits.

Secondly, under the PSA, the right to explore and extract resources can be granted over much larger areas than a standard special permit. The law even specifies an algorithm that allows combining several special permits into one area.

Thirdly, a legal freeze applies to investors involved in PSAs. This means that investors can only rely on the regulatory framework in place at the time of signing the agreement. Therefore, if parliament increases the profit tax or VAT, these changes will not affect the participants of the agreement. However, any legislative changes that favor investors will be applicable.

Fourthly, hydrocarbons extracted under the PSA are not subject to price regulation, unlike domestically produced oil or gas. This means that neither the operating company, Shell Exploration and Production Ukraine Investments (IV) B.V., nor the participants in Nadra Yuzivska LLC, will face price restrictions. Therefore, all hydrocarbons extracted under the PSA will be sold at the free market price, not at the domestic production price.

Another benefit is the potential export of hydrocarbons without being subject to the existing restrictions. As per the Cabinet of Ministers' Resolution No. 1201 of December 19, 2012, which approved the list of goods subject to licensing for export and import, there is a zero quota for the export of Ukrainian oil. The quota for gas is set according to the projected annual balance of receipts and distribution of resources approved by the government. Companies have the right to export gas or oil extracted under the PSA if it is commercially profitable.

Fifthly, there are no restrictions on foreign currency earnings for all parties to the agreement. Since November 15, 2012, the law of Ukraine "On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts Concerning Expanding Tools to Influence the Monetary and Credit Market" has been in effect, which mandates foreign trade entities to sell half of their foreign currency earnings within 90 days.

The PSA defines equal shares for the participants: Shell Exploration and Production Ukraine Investments (IV) B.V. – 50%, Nadra Yuzivska LLC – 50%.

Key concepts include compensation and profit-sharing production. For instance, once hydrocarbons start being extracted from the Yuzivska field, the process begins with compensating the costs of the parties through production. This is called compensation production, and its maximum amount, as specified in the agreement, is 65%. This means that from the first million cubic meters of gas, the distribution will not be 50/50. Instead, 650,000 cubic meters will be subtracted and allocated to the investor as compensation. The remaining 350,000 cubic meters will be divided between the parties based on the so-called R-factor calculation.

Challenges and Opportunities for Ukraine from the Production Sharing Agreement with the USA

Rare earth elements (REEs), which are discussed in the agreement proposed by the United States, consist of 17 elements from the periodic table: Scandium (Sc), Yttrium (Y), Lanthanum (La), Cerium (Ce), Praseodymium (Pr), Neodymium (Nd), Promethium (Pm), Samarium (Sm), Europium (Eu), Gadolinium (Gd), Terbium (Tb), Dysprosium (Dy), Holmium (Ho), Erbium (Er), Thulium (Tm), Ytterbium (Yb), and Lutetium (Lu).

People encounter these rare earth elements daily—they are found in smartphones, electric vehicles, solar panels, and are used in the production of coatings inside fluorescent lamps responsible for the color of emitted light. These elements are crucial in optics, lasers, the aviation industry, nuclear reactors, and even chemical catalysts for oil refining. And, of course, they are essential for the military industry.

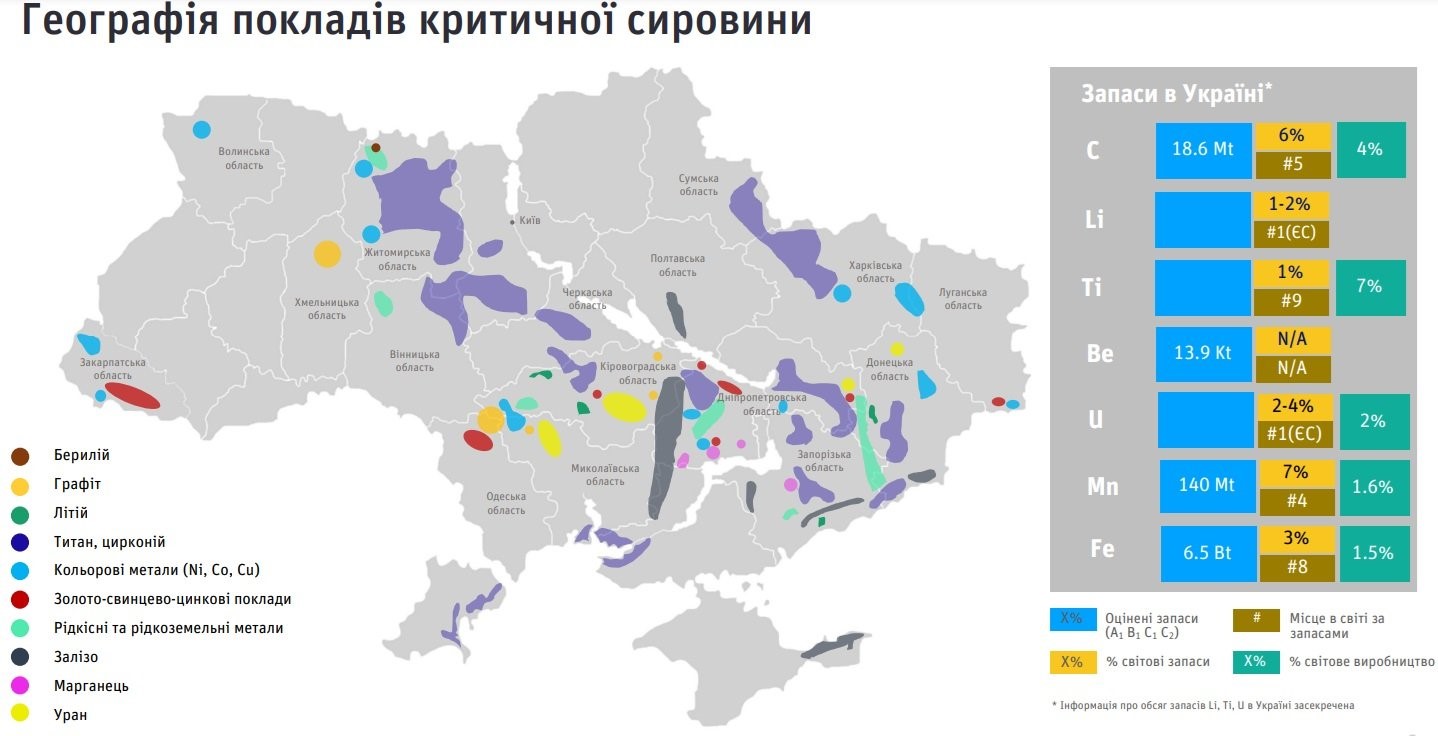

Currently, China is the global monopoly in the supply of rare earth elements, and for a long time, it has been dumping prices to prevent competitors from developing, including Ukraine. When, as a result of a trade war with the United States, China announced that it would stop selling rare earth elements, countries, including the United States, began to focus on securing their own resources. Due to competition with China and the desire for independence from the monopolist, the United States is actively searching for new deposits of rare earth metals. Besides China, deposits of rare earth elements are found in Australia, Russia, Brazil, Greenland, Canada, Vietnam, and recently, a large deposit was discovered in Norway (10% of global reserves). The localization of Ukrainian licensed areas for rare earth metals is shown in Figure 4.

From a geological perspective, Ukraine holds a treasure trove of minerals in the form of the Ukrainian Crystalline Shield, which is rich in valuable minerals, and the Donetsk-Dnieper Basin with hydrocarbon deposits. Structurally, Ukraine can be divided into the Ukrainian Crystalline Shield, the Donetsk Folded Region, and the Black Sea Basin. The Crystalline Shield is primarily rich in both metals and metalloids (semi-metals). The basins are abundant in hydrocarbons—coal, gas, oil—while the folded region contains both hydrocarbons and metals.

Ukraine has relatively few rare earth metals on the controlled territory, but the Russian-occupied Azov region is extremely rich in rare and rare earth metals (Figure 5), with the potential for industrial extraction. For example, the Mazurivske deposit of rare earth and rare metals such as zirconium, hafnium, niobium, and tantalum is located there. Additionally, the Mazurivske deposit of nepheline syenite is a subparallel vein system with a high content of rare minerals, which served as the industrial base for the Donetsk Chemical and Metallurgical Plant. Geologists referred to the Mazurivske deposit as an "exemplary" one. In general, the entire Azov region is a valuable resource in the context of rare and rare earth metals, as it is located on the southeastern megablock of the Ukrainian Shield. However, Mazurivka is in Volnovakha, which means it is currently under Russian occupation.

Conclusion

Overall, for Ukraine, this was a resource with promising development prospects because, in the old technological setup, it was not in demand, and we have not yet approached the new technological setup. Currently, this development is not feasible as the territory is under occupation. By the way, it is quite possible that Russia will begin the development of these natural resources, taking into account the industrial assets of Donbas that are under its control. Let’s not forget about the huge deposits of gas in compacted sandstones, which were commonly referred to as shale gas. What else makes Ukraine interesting to the United States in terms of resources? Experts highlight several areas:

- Uranium mining.

- Titanium mining.

- Graphite and germanium – metalloids.

- Lithium – an alkaline metal.

- Zirconium – a transition metal.

However, even all of this combined will not be able to cover the costs of U.S. assistance to Ukraine, especially since these are expensive to operate and technologically complex deposits. By the way, in the estimated value of our natural resources, which stands at 10 trillion USD, almost half of it is coal, which is not needed by America, as already demonstrated by the destruction of most thermal power plants (about 92% of installed capacity). Geographically, almost half of the natural resource deposits are occupied. Only within the framework of the absolutely fantastic project of "processing the Ukrainian shield" into its constituent minerals could we reach a value of several hundred billion dollars. But the cost of such "utilization" of the Crystalline Shield would be comparable to or even exceed the revenue. What is readily available in Ukraine is iron and manganese ore. These reserves are controlled by Ukrainian oligarchs and transcontinental companies. Approximately 5-7% of the Poltava Mining and Processing Plant (which has the best quality iron ore) is already owned by the American Blake Rock.